| William W. Coventry | home |

Lee At Gettysburg

A Critical Analysis of Aggressive Tactics

William Coventry

History 300

Jack Anderson

Table of Contents

Introduction 1

I will follow my native State with my sword and if need be with my life 3

A Battle had, therefore, become in a measure unavoidable 6

| I am going to whip them or they are going to whip me-------------- 9 |

A want of proper concert of action 13

I believed my men were invincible 17

Conclusion 20

General Robert E. Lee

Introduction

With the benefit of one hundred and thirty-three years of hindsight, it should appear easy to evaluate specific faults demonstrated by the tactics employed by the losing general. At Gettysburg, however, Lee's doomed designs came very close to producing a Confederate victory. He applied many of the same daring, aggressive tactics he used at Chancellorsville, fought only two months previously. What had changed or did not change, in Lee's tactics, that could make one battle a brilliant victory and the next a defeat costly enough to commence the road to Appomatix?

A combination of circumstances separated Gettysburg from Lee's previous battles. But he did not appear to be capable of adapting his modus operandi. Lee's reliance on aggressive tactics was simply not appropriate for the situation he stumbled into at Gettysburg. This is especially true when contrasted with the views expressed by his corp commanders. A more defensive orientation had a greater chance of ultimate victory for the Army of Northern Virginia. This paper examines Lee's failures to modify his tactics to fit the military circumstances, and why.

With certain exceptions, this paper will use only the most immediate, eyewitness primary sources. Unfortunately, Lee himself left only three documents to narrate his version of the battle. (Gallagher, Third Day 33) As the defeat at Gettysburg gathered significance as a turning point in the war, Confederates looked for someone or something to blame. Everyone had an opinion about, and excuse for, their loss. Even Jefferson Davis indirectly criticized Lee's aggressive tactics when he wrote "had Lee been able to compel the enemy to attack him in position, I think we should have had a complete victory."(Jones 170)

The acrimony, partisanship and fingerpointing, especially after the death of Lee, makes later "memoirs" highly circumspect. Stuart, Longstreet and Ewell are particularly targeted for blame. Southerners, tended to only look amongst themselves for the reasons behind their defeat - refusing any credit towards Union prowess or ability. When asked to explain the demise of his "charge", General Pickett proved to be an exception. He replied, " I believe the Union Army had something to do with it." (Gallagher, Third Day 84) This paper aspires to be as honest and impartial as Pickett.

I will follow my native State with my sword,

and if need be with my life

The Confederacy never sustained one set "Grand Strategy". (Nolan 77) Their goal was independence from the United States. As Jefferson Davis stated in April, 1861 to his Congress, "...all we ask is to be left alone." (Thomas, Confederate Nation 104) Lee echoed this sentiment. (Dowdey 363) To achieve this, the Confederacy tried various methods and strategies. They could win simply by not losing. As long as the its Government and its armies existed, they were free. (Nolan 70)

In theory, given the North's overwhelming preponderance in population and economic might, the South should have relied on a strictly defensive policy. Similarities to Washington and his successful strategy during the American Revolution were drawn.5 This view was shared by E.P. Alexander, chief of ordnance of the Army of Northern Virginia (who incidentally directed the artillery bombardment preceding Pickett's Charge).Alexander wrote :

| When the South entered upon war with a power so immensely her superior in men & money, & all the wealth of modern resources in machinery and transportation appliances by land & sea, she could entertain but one single hope of final success. That was, that the desperation of her resistance would finally exact from her adversary such a price in blood & treasure as to exhaust the enthusiasm of its population for the objects for the war. We could not hope to conquer her. Our one chance was to wear her out. (Nolan 70) |

The culture and society of the South, however, were not conducive to passively relying on the defensive. Clausewitz's dictums concerning war as a continuation of policy and comparing a nation's warfare to its national character applied strongly to the Confederacy. (Keegan 5-13) Pride, provincialism and a tendency to resort to violence were characteristics of the Old South. The caning of Charles Sumner by South Carolinian Preston Brooks is a classic example of these traits. (Thomas, Confederate Nation 105-6)

For the North to preserve the Union, it would have to invade and subjugate the South. (McWhiney & Jamieson 6) With such a small population and limited resources, the South could not defend all its enormous territory simultaneously. A more offensively oriented strategy, better mirroring public opinion and temperament, was considered necessary. (Thomas, Confederate Nation 105-6) As Confederate Colonel W.C.P. Breckinridge wrote :

...it was the fated of the Southern armies to confront armies larger, better equipped and admirably supplied. Unless we could by activity, audacity, aggressiveness, and skill overcome these advantages it was a mere matter of time as to the certain result. It was therefore the first requisite of a Confederated general that he should be willing to meet his antagonist on these unequal terms, and on such terms make fight. He must of necessity take great risks and assume grave responsibilities. (McWhiney & Jamieson 18)

According to McWhiney and Jamieson's book, Attack and Die : Civil War Military Tactics and the Southern Heritage, this offensive thinking was shared amongst the highest ranks of the Confederate army. All of the commanding generals of the two largest armies of the South (excepting Joseph Johnston) believed the key to independence lay in offensive tactics. These were generals Lee, Bragg, Hood, Beauregard and A.S. Johnston. Joseph Johnston wound up being heartily maligned, from President Davis on down, as being inept, traitorous, cowardly, etc. (McWhiney & Jamieson 161)

General Robert E. Lee was, and is, considered to be the very embodiment of aggressive tactics. It is interesting to compare two evaluations of him as he assumed command. After stating he preferred Lee to Johnson as an easier opponent, George McClellan appraised Lee as, "...too cautious and weak under grave responsibility ... wanting in moral firmness when pressed by heavy responsibility, and ... likely to be timid and irresolute in action." (Woodworth 151)

A far more fitting description of Lee was done by Joseph Christmas Ives, a member of Davis' staff. He told E.P. Alexander, "... if there is one man in either army, Federal or Confederate, who is, head & shoulders, far above every other one in either army in audacity that man is Gen. Lee, and you will very soon have lived to see it. Lee is audacity personified." (Thomas, Lee 226)

For the next three years, Lee demonstrated his audacious nature. Within three days of his assuming command of the Army of Northern Virginia he wrote to Davis, outlining a daring strategy.

After much reflection I think if it were possible to reinforce Jackson strongly, it would change the character of the war. This can be only be done by the troops of Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina. Jackson could in that event cross Maryland into Pennsylvania. It would call all the enemy up from our southern coast and liberate those states. (Dowdey & Manarin 183-84)

Here we see the seeds of the strategy that would lead to Gettysburg. The plans and reasons for invading the North were becoming concrete. These were not the proposals of a cautious, timid and irresolute general. Due to the machinations of the Federal army, however, it would be eleven months before he could bring his forces into Pennsylvania. By that time, Jackson would be dead. But Lee's audacity was making their army feared and famous.

A Battle had, therefore, become

in a measure unavoidable

After nearly a year of battling the Army of the Potomac, the opportunity arose for a strike into the North. Lee's skillful victories in the east were being undermined by trouble in the western theatre. Vicksburg was in serious trouble. After Chancellorsville, the Confederate administration thought it was time to detach part of Lee's army for service out west.

Lee realized his victory at Chancellorsville had been very costly - as were all his "victories". In addition to losing Jackson, his "right arm", the Army also sustained thirteen thousand casualties - twenty-one percent of his total. (Nolan 85) With the transfer of any sizable amount of the troops to the west, Lee would lose his ability to operate offensively. He would be forced into a siege of Richmond , which he feared would inevitably lead to starvation and surrender. (Dowdey 356) Lee's aggressive instincts could not let this happen. According to General Henry Heth, Lee stated, "I considered the problem in every possible phase, and to my mind it resolved itself into a choice of one of two things - either to retire to Richmond and stand a siege, which must ultimately have ended in surrender, or to invade Pennsylvania." (Nolan 85)

Lee went to Richmond in May to try to convince the administration to back a more daring plan. Though Davis and his Cabinet were skeptical, Lee's confidence, reputation and reasoning bought nearly all of them around.(Gallagher, Lee 168) As Alan Nolan relates, the true goal was to fight the Federals on their own soil. Nolan writes:

The numerous reasons for the campaign offered by Lee and the commentators are well known: the necessity to upset Federal offensive plans, avoidance of a siege of the Richmond defenses, alleviation of supply problems in unforaged country, encouragement of the peace movement in the North, drawing the Federal army north of the Potomac in order to maneuver, even the relief of Vicksburg. Some or all of these reasons may have contributed to the decision, but fighting a battle was plainly inherent in the campaign because of the foreseeable Federal reaction and because of Lee's intent regarding a battle. (Gallagher, First Day 10)

This was not viewed, in any way, as a desperate move by Lee. This was the best way he believed he could win the war. As Lee saw it, the North would eventually defeat the South by virtue of simple economics and population. Unless he could take the initiative, invade the North, and accomplish his objectives, the war could be lost. And he was right.

The army set out in June. It had been reorganized to make up for some of the losses taken and deficiencies demonstrated in previous battles. Lee tried to compensate for all the officers and men lost at Chancellorsville. He refilled the officer posts with new men and scrounged for replacements from any Confederate army he could. There was now three corps instead of two. The Calvalry and Artillery had also been reorganized. (Coddington 11-18) For a gamble of this gravity, Lee wanted the playing field to be as equal as possible. These men were going north to violently prove a point - that the North could be invaded as well as the South. As Lee wrote Davis less than a week before Gettysburg : "It seems to me that we cannot afford to keep our troops awaiting possible movements of the enemy, but that our true policy is, as far as we can, so to employ our own forces as to give occupation to his at points of our selection." (Dowdey & Manarin 532)

A sense of overconfidence and invincibility had permeated throughout the Confederate army. From the commanding general down, throughout the ranks, they were beginning to believe they could not lose. They attributed their victories to their military prowess and "righteousness" of their cause. As British observer Arthur Freemantle wrote, that, apart from Longstreet, "the universal feeling in the army was one of profound contempt for an enemy whom they had beaten so constantly, and under so many disadvantages." (Gallagher, Second Day 30-31) This overconfidence played a role in the inept, uncoordinated way this battle was both begun and fought. Lee's army was dispersed throughout enemy territory, without any reliable method of intelligence gathering. Though they knew the Federals must pursue and confront them, their actions demonstrated a shortsighted lack of appreciation for the danger inherent in the Army of the Potomac.

Though this lack of intelligence tends to be blamed on Stuart alone, his orders were discretionary enough for him to capture Federal wagons on the far side of the Union Army. There was no specific time schedule or route. (Gallagher, First Day 142-43) Lee had to receive his information through a spy - a system he believed highly unreliable. The spy, Harrison, gave Lee the approximate location of the Federal army, along with the name of their new commander, George Meade. Lee then presciently stated, "General Meade will commit no blunder in my front, and if I make one he will make haste to take advantage of it." (Thomas, Lee 293)

These "blunders" were about to begin. Though Stuart was missing, Lee still had enough cavalry, albeit second-rate, to perform basic intelligence gathering. But Lee failed to employ them appropriately. (Gallagher, Lee 455) Lee did not want to stumble into a general engagement without his troops being concentrated. But his orders were vague enough for a battle of enormous consequences to be commenced accidentally - without reliable knowledge of the terrain or enemy strength. (Coddington 309) Lee's impetuosity was apparent once he reached the battlefield. When he first conferred with Heth, Lee refused to allow him to continue his attack. Yet once he surveyed Rodes' men preparing to attack the tenuously-held Federal position, Lee changed his mind. (Pfanz, Culp's Hill, 40) Lee's aggressive tendencies took over, though he still did not know the enemy's strength.

This is not to say Lee was wrong in fighting this engagement. Many battles are won or lost by this kind of instantaneous decision making. There is rarely enough military intelligence to make any battle a sure thing. There are too many variables and opportunities. In fact, the first day of Gettysburg could be considered a Confederate victory. Both Lee and Meade had fumbled into battle. To paraphrase Nathan Bedford Forrest, Lee had gotten there "first with the most". (Sifakis 225) The Federals had been driven from the field. Lee had gambled again and it appeared, on the night of June 1st, that he had won. Over on Cemetery Ridge, however, part of Meade's army was fortifying as the remainder marched to Gettysburg.

I am going to whip them or they are

going to whip me

As Lee watched the Federals pull back, he naturally wanted to expand this retreat into a rout. He could appreciate the value of the high ground on the other side of town. He asked Hill to continue the advance, but Hill declined. His men, he reported, were "...exhausted by some six hours of hard fighting [and that] prudence led me to be content with what had been gained, and not push forward troops exhausted and necessarily disordered, probably to encounter fresh troops of the enemy." (Gallagher, First Day 27)

To continue the offensive, since Longstreets troops were not up yet, Lee turned to Ewell. Lee sent a message to take the hill "if practical". (Gallagher, Lee 456) The leeway involved with the phrase "if practical" was demonstrative of Lee's command style - as well as his apprehension over what troops Ewell might face. The "eyes and ears" of the army, Stuart, was missing.

As Lee waited for Ewell to press an attack that would not materialize, Longstreet rode up. To Longstreet, the Federal retreat presented the Confederates with a perfect opportunity to employ the defensive strategy he hoped his commander would follow. As Longstreet wrote in "Lee in Pennsylvania" (published 1879, fourteen years after Gettysburg):

When I overtook General Lee, at five o'clock that afternoon, he said, to my surprise, that he thought of attacking General Meade upon the heights the next day. I suggested that this course seemed to be at variance with the plan of the campaign that had been agreed upon before leaving Fredericksburg. He said: "If the enemy is there tomorrow, we must attack him." I replied: "If he is there, it will be because he is anxious that we should attack him - a good reason, in my judgment, for not doing so." I urged that we should move around by our right to the left of Meade, and put our army between him and Washington, threatening his left and rear, and thus force him to attack us in such position as we might select. (Gallagher, Lee 388)

Lee put no faith in this plan, though Longstreet clung to it for the next three days. For one thing, after Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, Lee may have assumed the Federals had smartened up. With Meade in charge, Lee might not expect innovative Federal tactics, but he could reasonably anticipate no blunderous ones.

Feeling impatient, Lee rode over to Ewell's headquarters. He noticed Ewell's men were preparing for bivouac instead of assault. (Dowdey 369) After just speaking to Hill and Longstreet, the battle-ready Lee was distressed. His offensive plans, so dependent upon speed and momentum, appeared to have been postponed - without his direct knowledge or approval. Walter Taylor, a member of Lee's staff, wrote:

The prevailing idea with General Lee was, to press forward without delay; to follow up promptly and vigorously the advantage already gained. Having failed to reap the full fruit of the victory before night,his mind was evidently occupied with the idea of renewing the assaults upon the enemy's right with the dawn of day on the second. (Gallagher, Second Day 22)

Lee met with Ewell, Rodes and Early. Early apparently did most of the talking. Lee's interest, Early wrote, was "to attack the enemy as early as possible next day - at dawn if practical." (Pfanz, Culp's Hill 83) Early then described the difficulties the Confederates would face, specifically the terrain and the Federal's strongly held position. (Pfanz, Culp's Hill 83) Early then reasoned the Confederates would have a better chance of success by attacking Meade's left flank. Ewell and Rodes agreed. A disappointed Lee replied, "Then perhaps I had better draw you around toward my right, as the line will be very long and thin if you remain here, and the enemy will come down and break through it?" (Pfanz, Culp's Hill 83)

Lee's generals hastily disagreed. The morale of the troops would suffer if they were removed from positions they had fought so hard to take. The difficult terrain of the area would help protect the Confederates from attack. Leaving his Second Corp where they were would allow his men and their morale to be relatively safe. But what good to Lee was that? He knew Hill's men were weary and disorganized from the day's battle. He knew Longstreet was against an offensively fought battle, even before the First Corp had arrived on the field. But the First Corp was fresh and slowly becoming available. Lee reluctantly told Ewell the attack would be made by Longstreet's men. (Pfanz, Culp's Hill 84)

At this point, Lee must have felt discouraged. As at Chancellorsville, he believed he defeated the Union army, driving it from the field in disarray - but not destroying it. And that was with Jackson. How many more chances would he get like these? Now, however, each of his corp commanders were uninterested in pressing the attack - at least by their own corp. They each had their own reasons, many valid and understandable. It appeared to Lee that the only thing needed for victory now was for his subordinates to take the initiative and push "those people" off that position.

Lee himself had shown no interest in finding a defense oriented position. His men had almost carried the battle. Lee had seen the Federals, once again, retreat. Once again his men were slowed and "burdened" by taking prisoners. His faith and confidence in his men were unshakable. (Roland 146) Just recently they had fought in Lee's most brilliant battle, Chancellorsville, against longer odds. Southern valor and elan had once again routed their foes. Lee's tactics were to remain the same - attack as soon as practical. He knew the Federals were concentrating and fortifying - making time as well as terrain and numbers an enemy of the Confederacy. But which corp should he use, and where, when no corp commander seemed interested, much less enthused, about leading the attack?

Shortly after Lee returned to his headquarters, he decided Ewell's men would be useless defending a position he did not need. He sent Marshall over to order Ewell that, unless Ewell would attack, Lee "...intended to move Longstreet around the enemy's left & draw Hill after him, directing Gen'l. Ewell to prepare to follow the latter." (Pfanz, Culp's Hill 84) Ewell discussed the order with Early, then, despite the late hour, rode over to speak with Lee. He would attack. Lee became relieved and determined. (Dowdey 372) Ewell would coordinate with Longstreet. A.P. Hill would threaten the Union center. Here was the aggressive spirit Lee wanted to see. He had not intended to invade the North just to find a nice safe position to starve in.

Lee's plans reverted to what he had originally intended. Once again, "we will attack the enemy as early in the morning as possible." (Dowdey 372)

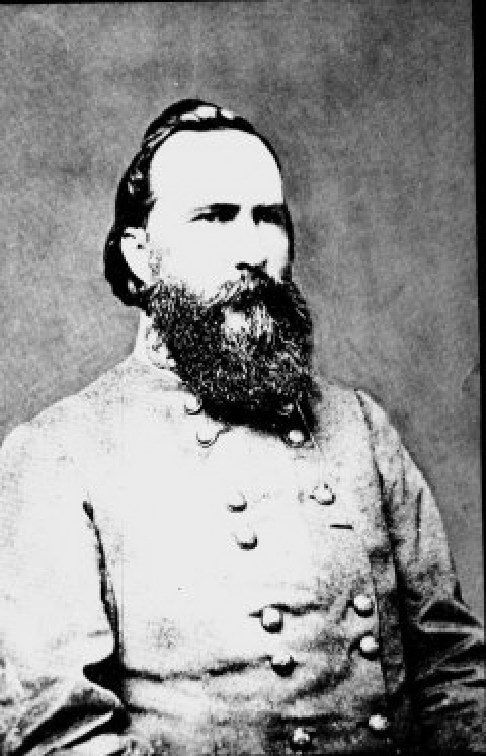

General James Longstreet

A want of proper concert of action

Captain Justus Schiebert, an observer for the Prussian army, had an opportunity to speak to Lee about the general's command style - a mere three days after Gettysburg. Schiebert relates Lee stated, "I plan and I work with all my might, to bring troops to the right place at the right time; with that, I have done my duty." (Stewart 84-85) For Lee to intervene "...does more harm than good" and he must "...leave the matter up to God and the subordinate officers." (Gallagher, Third Day 43) This interpretation of how Lee considered performing his "duty" would have catastrophic consequences at Gettysburg.

During the previous year, this style of managing an army had worked surprisingly well. At Gettysburg, however, two of his three corp commanders were new to the position. This inexperience trickled down throughout the officer ranks as many replacements were needed after Chancellorsville. Neither Hill or Ewell had shown much promise the first day. Though the Federals had been driven from the field, it was largely due to fortunate timing and luck. No brilliance had been displayed. No innovative tactics had won the day. These men had proven that, even combined, they were not the equal in battle command ability to one Jackson.

The discretionary orders Lee used to bring out the best in Jackson were not specific enough for these generals. For a battle of this magnitude, Lee would need to outline orders concisely to achieve the results he desired. Supervision would be especially essential as Lee planned for his forces to attack entrenched superior forces - in enemy territory. There would be no margin for errors. Yet Lee could not change his command style.

Ewell and Hill had served under Jackson - whose orders left no room for independent maneuvering. To Lee, allowing his subordinates room for independent tactics demonstrated his trust. To Jackson, this could easily lead to court-martial. These corps commanders were neither incompetent nor cowardly. Used to more direct, supervised orders, they would need some time and experience to adjust to Lee's style. But the second day of July, 1863, was not the day to learn.

This leads us to James Longstreet. Longstreet was used to Lee's command style. Unfortunately, it appears he considered Lee as kind of a co-commander - not as a superior officer. With Lee considering only attack as a plan and Longstreet committed to fighting a defensive battle, tactical planning became fractured and argumentative. Both believed they knew the best way to beat the Federals, but they held opposing viewpoints. Right up to the Pickett-Pettigrew charge, Longstreet had no interest in launching aggressive strikes. He did them, of course, but hesitantly and without enthusiasm.

Since these generals had never worked together as corp commanders (or even got along well with each other) and barely agreed with Lee's tactics, a meeting was needed. Coordination would be the key to fighting this battle, either making or breaking it. The interior lines of the Federals, with their ability to move men and artillery from point to point relatively easily, would prove murderous to any disjointed Confederate attack. Though this appears obvious, the Confederates could not seem to achieve this crucial goal.

Lee was up before four, making sure his men were going to be "at the right place, at the right time." Along with everyone else, he realized the Federals had been fortifying their positions and gathering more troops. After dawn, as Ewell waited for the sound of Longstreet's guns to open the battle, the recalcitrant First Corp commander rode up to Lee to again argue his defensively based strategy. Lee simply walked away. (Thomas, Lee 296-97)

After waiting several hours, Lee rode in search of Longstreet. Finding him around 11 a.m., Lee was finally forced to order Longstreet to attack. (Thomas, Lee 297) Which Longstreet did, approximately five hours later. Three weeks after the battle had been lost, Longstreet wrote," I consider it part of my duty to express my views to the Commanding General. If he approves and adopts them, it is well; if he does not, it is my duty to adopt his views, and to execute his orders as faithfully as if they were my own." (Pfanz, Second Day 26) Unfortunately for Longstreet's men, and the Confederacy as a whole, he did not follow his own words at Gettysburg.

As Lee would not listen to his "sounder" advice, Longstreet would be forced to follow Lee's orders. But he would follow them slowly, stubbornly and with murderous consequences. Instead of using the latitude of the orders to aggressively attack the Federals as best he could, Longstreet used the leeway to muddle and slow the offensive - thereby willfully sending his own men in to be slaughtered. The fact that his men valiantly took Big Round Top and Devil's Den, and almost took Little Round Top and The Wheatfield did not seem as important to Longstreet as proving himself correct.

For the Third Corp, with Hill sick, Pender down with a mortal wound and Heth down with a near mortal one, no real "threatening" of the Union center occurred. (Dowdey 380) Without forceful leadership, their attack never made it off the ground.

As far as the Second Corp was concerned, the real fighting did not start until approximately six in the afternoon. Held on by General Greene's brigade (the other Union troops had been pulled out to help defend the Union left), the terrain proved so rocky, hilly and wooded that his troops held the Confederates until dark. The Confederates took over some of the vacated Federal trenches, but that was all. (Coddington 430-32)

Lee's orders for "attacking as early as possible, preferably dawn" had been mismanaged, ill-timed and possibly even sabotaged by his own subordinates. Although thousands of Confederate casualties littered the ground from Little Round Top to Culp's Hill, no "good ground" had been taken.

Lee himself was on Seminary Ridge, doing his duty by trusting his subordinates. He received one message and sent one. Most of the time he sat dispassionately on a stump. (Roland 146) From the very limited view his fieldglasses gave him, Lee saw nothing that demonstrated his reliable, aggressive tactics were not working. (Thomas, Lee 298) Unlike their usual custom after a battle, that evening Lee and Longstreet did not meet. Once again, as Lee wrote out his orders, he decided his best hope lay in attack. Once again, Longstreet was opposed. (Dowdey 382)

The following day, Longstreet, supported by elements of Hill's corps, was to crack the Union center. Ewell, at the sound of Longstreet's guns, would attack Culp's Hill and Cemetary Hill. (Roland 144) Stuart, who had arrived mid-afternoon on the second, would ride around the Federal army and hit them in the rear. The Federals would be split, their disorganized and broken army ripe to be routed. (Coddington 520)

Lee still had one fresh division left, Pickett's. It was a bold plan, even reckless. Yet the war could be won by afternoon. Lee decided his aggressive gamble was well worth the risk.

Federal dead in the Peach orchard

Confederate dead, Devil's Den

I thought my men invincible

At first light on July third, Lee rode over to discuss the proposed assault with Longstreet. As their communication the previous night had been done by courier, Lee wanted to make sure his subordinate understood the plans. (Gallagher, Third Day 38) Lee's orders had again called for early morning, concerted attacks.

Longstreet, however, had different plans. He proposed to circle around the Round Tops, striking the Union line from the rear. (Gallagher, Third Day 37) He had already given orders for the attack. On arrival, an annoyed Lee immediately canceled the movement. (Piston 58-59) Lee then sent a courier to postpone Ewell's attack until Longstreet was ready. (Dowdey 385) After discussion with Longstreet, Lee did allow the divisions of Hood and McLaws to stay in the positions they had fought so hard for the preceding day, substituting some of Hill's troops in their place. (Gallagher 31-32)

The Federal troops at Culp's Hill, angry at having their trenches taken over by the enemy, were in no mood to wait for any concerted, Confederate attack. They surprised the rebels by attacking first. Once again, Lee had lost the initiative. The battle was taking another unexpected turn.

Lee, A.P. Hill and Longstreet rode over the field, deciding troop dispositions. (Thomas 299) During the previous day, their lack of communication and coordination had cost them bitterly. Even Lee's devoted biographer Douglas Southall Freeman stated it appeared as if there was no acting commander-in-chief the previous day. (Roland 145) Lee must not make that mistake on the third.

After several hard fought hours, the battle for Culp's Hill and Cemetary Hill was over. The Federals were simply too entrenched for the Confederates to take their position. A Union countercharge finally drove them from their works. Once again, the concerted action Lee required failed to materialize. Employing his interior lines, Meade was free to concentrate his forces wherever they were needed. (Pfanz, Culp's Hill 352)

Shortly after one p.m., one hundred and forty three guns of the Confederacy bombarded the Union line, mostly at the center. (Stewart 114-15) Though at one point Lee rode in front of Pickett's line, he could no longer alter events. (Stewart 144) At this point he had delegated control of the battle to Longstreet, who believed it was doomed. Longstreet appeared eager to pass off his responsibility and authority to Pickett and Alexander. (Piston 59-61) After forty five minutes of an intense cannonade, projected to decimate the Union center and opposing artillery batteries, Longstreet reluctantly acquiesced to have Pickett's men attack. (Piston 60-61)

For Lee, this was his greatest gamble, an attack of Napoleonic dimensions. To break the Union line could mean decisively defeating the enemy on it's own soil - with enormous political repercussions. This could lead to Confederate independence. A defeat, however, could mean the destruction of his army, or at least the end of his Pennsylvanian campaign. Defeat or victory, it would result in a large number of casualties - which his knew the Confederacy could not make up. Just before the cannonade, he quietly stated "the attack must succeed." (Stewart 108) As Lee watched from Seminary Ridge, the Confederates marched out from the woods.

For approximately an hour, Lee viewed a sight of glorious pageantry dissolve into butcherous horror and defeat. As he watched his repulsed troops straggle back to Seminary Ridge, the magnitude of his failed gamble confronted him. "It has all been my fault" he told generals and privates alike. (Thomas 300) Whether he meant the Gettysburg campaign as a whole or simply the assault he did not say.

The toll was disastrous for the Confederacy. Total casualties for their assault is estimated at 6,467 men, or about sixty two percent of the men engaged. Generals Garnett and Armistead were dead, Kemper and Trimble were out for the remainder of the war. In Pickett's division, thirty-one out of thirty-two field officers were casualties. (Stewart 263-68)

For Gettysburg as a whole Lee sustained 22,638 casualties out of 75,054 men engaged, a startling 30.2 % casualty rate. (McWhiney & Jamieson 8) This figure alone demonstrates Lee's aggressive tactics were crippling to the Confederate army. The fact that Lee lost the battle makes the statistics even more disastrous.

There was nothing left but to retreat to Virginia. Gettysburg had cost the Confederacy prestige and a huge loss of manpower. Lee's army would fight on for another two years. But on the other side of the Confederacy, a general with Lee's aggressive nature was just receiving the surrender of Vicksburg. The critical difference was that this man had the strength of the Northern economy and manpower to support him.

Conclusion

In a thought-provoking study, Lee's renowned biographer Douglas Southall Freeman writes of nine qualities that gave Lee the victories and reputation he deserved. In R.E. Lee : A Biography, Freeman summarizes :

| These five qualities, then, gave eminence to his strategy - his interpretation of military intelligence, his wise devotion to the offensive, his careful choice of position, the exactness of his logistics, and his well-considered daring. Midway between strategy and tactics stood four other qualities of generalship that no student of was can disdain. The first was his sharpened sense of the power of resistance and of attack of a given body of men; the second was his ability to effect adequate concentration at the point of attack, even when his force was inferior; the third was his careful choice of commanders and troops for specific duties; the fourth was his employment of field fortifications. (Gallagher 147) |

It is sadly obvious how these qualities were missing or misused during the Gettysburg campaign. The only military intelligence he received and interpreted was given to him by a spy. Though the information turned out to be correct, Lee still blundered into a battle. Lee's devotion to the offensive could not be considered "wise" at several times, if at all. This corresponds to his "daring". His choice of preferred position was correct, unfortunately the Federals were already there and fortifying. The "exactness" of his logistics was a farce, as Lee was forced to bring up his troops and equipment piecemeal. He was then forced to throw them into a progressively larger battle as circumstances beyond his control dictated.

His "sharpened sense of the power of resistance and of attack of a given body of men" was dulled by his underestimation of the valor and stubbornness of his opponents throughout the battle - egregiously demonstrated during the Pickett-Pettigrew charge. For two days he had bitterly battled the Union at ridge and run, orchard and field, hill and wood. Yet he continually, obstinately misjudged Federal determination and resistance. His attempts at "concentration at the point of attack" failed him as well. Confederate coordination was so poor that men did not come to the aid of their nearby compatriots simply due to poor orders and staffwork. His "careful" choice of commanders and troops for "specific duties" was again abysmal. His reliance upon Longstreet for aggressive, timely attacks and his employment of nearly decimated divisions for decisive engagements (i.e. Heth's division at the Pickett-Pettigrew charge) demonstrated either carelessness or an overwhelming confidence in his tactics. Finally, the only field fortifications the Confederates saw were the ones they fought against. At Culp's Hill, they did manage to secure some abandoned Federal trenches. But that was all.

Lee's proper exercise of these nine qualities had make him a superb general. But when they were absent, as at Gettysburg, defeat was almost certain. Lee, however, did not seem to grasp that Gettysburg was a battle altogether different from the ones he had fought previously. He did not appear to realize the problems inherent in his offensive-only tactics. Though Lee's later statements are all second-hand testimonies, never written by Lee himself, they all essentially agree. Though Lee honorably places the blame of failure upon himself (as the commander-in-chief should do), he never admits his tactics were faulty. They simply were not carried out as Lee envisioned. Which was true.

Hours after he told his troops "It was all my fault", Lee told General Imboden :

| I never saw troops behave more magnificently than Pickett's division of Virginians did to-day in that grand charge upon the enemy. And if they had been supported as they were to have been, - but, for some reason not fully explained to me, were not - we would have held the position and the day would have been ours. (Thomas, Lee 301) |

Lee obviously believed the charge could have been, and should have been, successful. When writing to Major William McDonald about the battle, Lee summarized his interpretation of events:

| I must again refer you to the official accounts. Its loss was occasioned by a combination of circumstances. It was commenced in the absence of correct intelligence. It was continued in the effort to overcome the difficulties by which we were surrounded, and it would have been gained could one determined and united blow have been delivered by our whole line. (Gallagher, Second Day 9-10) |

Starting with the first obvious possibility, what if Ewell (or Jackson, for that matter) had captured Cemetary Hill. This is a perfect example of Lee's vision of daring offensive tactics. Alan Nolan, however, presents a compelling case for the correctness of Ewell's decision. First Nolan states the numbers of Federal troops on or near Cemetary Hill. Then Nolan quotes the Confederate opinions of the situation. That the Federals were fortifying their position was no secret. After General Rodes pushed the Union troops through Gettysburg, he noticed that even before:

the completion of his defeat before the town, the enemy had begun to establish a line on the heights back of town, and by the time my line was in a condition to renew the attack, he displayed quite a formidable line of infantry and artillery immediately in my front, extending smartly to my right, and as far as I could see to my left, in front of Early. (Gallagher, First Day 26-27)

The condition of the troops, exhausted, disorganized and battle-weary has already been mentioned. A Jackson may, or may not, have been able to capture the heights. But would they have been able to hold it? The last time Jackson had pushed his troop (exhausted, disorganized and battle-weary) to victory, he had been mortally wounded.

This is the key to the "what ifs". If Culp's Hill, Little Round Top or even the Union center on Cemetary Hill had been taken, would the Confederates be able to exploit the breech? Reserves had been noticeably missing or not used effectively throughout the battle. Meade had the interior lines and approximately eighty-four thousand troops (casualties not included). (McWhiney & Jamieson 19) They were amply supplied, reasonably fortified and defending their own soil. If Oates had knocked Chamberlain back across Little Round Top, he had little support to exploit his success. Even if the mighty Jackson was alive to break the Union center instead of Longstreet, and even if he had ten times the amount of men that overran the Angle, how long could they have lasted?

Lee's confidence in his own ability, and that of his army, had become unrealistic, or at least idealistic. Using the best case scenario, with the Federals broken and routed, how long could Lee's battered force, with little supplies, capture and hold a city such as Washington or Philadelphia? Lee continually expected the Federals to break and run, even as they flagrantly demonstrated their courage, strength and stubbornness. He knew his men could match these Federal qualities, but, due to terrain and numbers, would have to surpass this. With proper generalship, intelligence and coordination, it was possible. But he did not have this, and realized it from July 1st onwards.

Lee understood his difficulties. But he could not change his command style, or his aggressive tactics. Lee knew the stakes he was fighting for, either independence or forced "re-admission" into the Union. He knew, victory or defeat, that his casualties would be very great - and for the Confederacy, irreplaceable. He knew he was fighting a battle of enormous consequence, before his army was concentrated, the terrain examined, and the enemy surveyed. He knew his corp commanders, especially after July 1st, were no Jacksons, or even Longstreet at his best. They were all against taking the offensive. Lee had to work quickly to alter and adapt his management style to win at Gettysburg. But he could not. Unfortunately for the Confederacy, Lee's aggressive tactics were not appropriate for the Gettysburg campaign.

Three Confederate Prisoners after Gettysburg

Works Cited

Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1968.

Dowdey, Clifford. Lee. Boston: Little, Brown And Company, 1965.

Dowdey, Clifford and Manarin, Louis H. The Wartime Papers of R.E. Lee. New York: Bramhall House, 1961.

Gallagher, Gary H., ed. The First Day at Gettysburg. Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 1992.

---, ed. The Second Day at Gettysburg. Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 1992.

---, ed. Lee: The Soldier. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1996.

---, ed. The Third Day at Gettysburg and Beyond. Chapel Hill, North Carolina. 1994.

Jones, Archer. Civil War Command and Strategy - The Process of Victory and Defeat. New York: The Free Press, 1992.

Keegan, John. A History of Warfare. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994.

McWhiney, Grady and Jamieson, Perry D. Attack and Die - Civil War Military Tactics and the Southern Heritage. University, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1992.

Nolan, Alan T. Lee Considered: General Robert E. Lee and Civil War History. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg - Culp's Hill and Cemetary Hill. Chapel Hill: London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

---. Gettysburg - The Second Day. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 1987.

Piston, William Garrett. Lee's Tarnished Lieutenant : James Longstreet and His Place in Southern History. Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press, 1987.

Roland, Charles P. An American Iliad: The Story of the Civil War. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 1991.

Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts on File Publications, 1988.

Stewart, George R. Pickett's Charge: A Microhistory of the Final Attack at Gettysburg, July 3, 1863. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1987.

Thomas, Emory M. The Confederate Nation 1861 * 1865. New York: Harper Colophon Books, 1979.

---. Robert E. Lee. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1995.

Woodworth, Steven E. Davis & Lee at War. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1995.