| William W. Coventry | home |

|

|

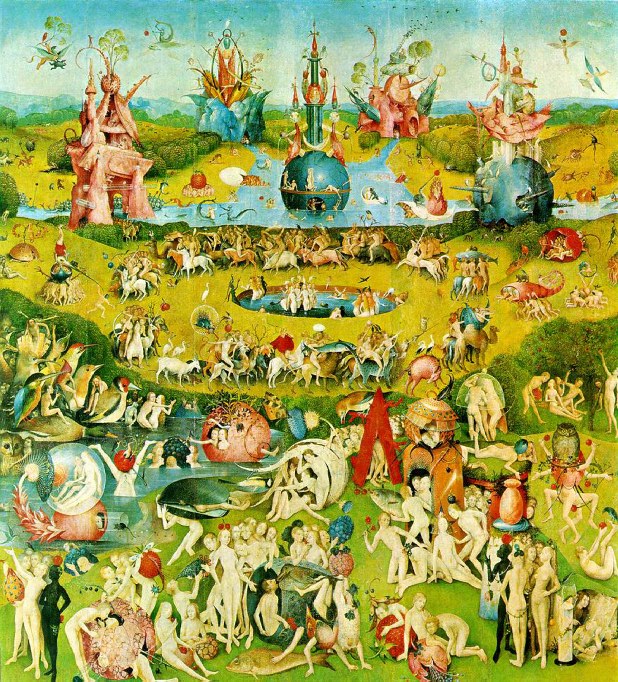

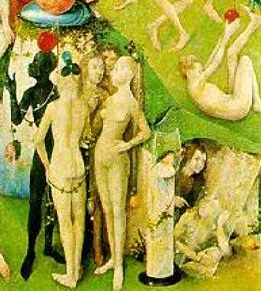

| Center Panel (The Garden of Early Delights) |

|

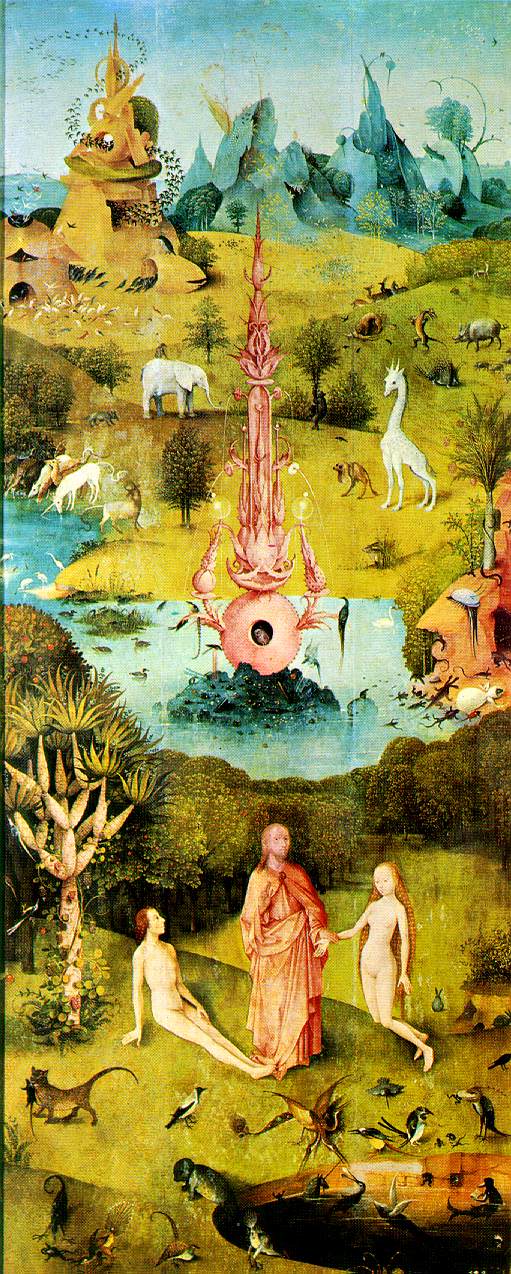

| Left Panel (heaven) |

|

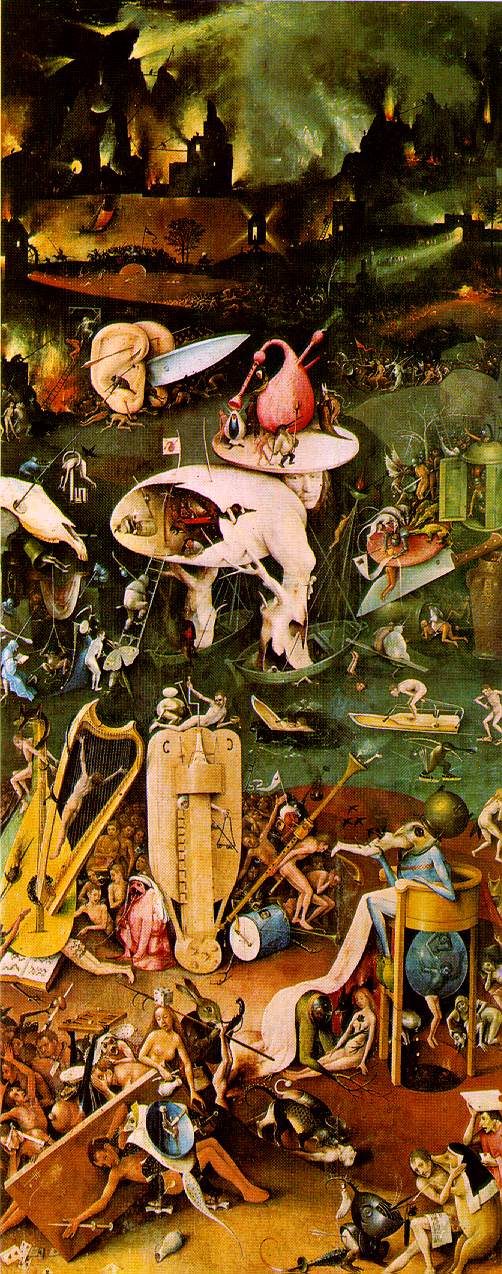

| Right Panel (hell) |

|

Introduction

From kings to commoners, bishops to heretics… in fact, all those who have studied a painting by Hieronymus Bosch have come away with his or her own interpretations of the meaning of his work. His style is so unique, his representations so original, his creative output so fanciful that one is left simply dazzled. For the past five centuries, people have tried to unlock the elusive significance behind his aesthetic symbolism. Unlike his contemporaries Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dòrer, Bosch left no letters, diaries or writings of his own. His paintings are not dated. Nearly everything known about him is actually guesswork and interpretation. His artistic capability, his technical expertise, his genius, his fears and his outlook on mankind's ultimate future are all presented in his works. The symbolism, however, (deeply crucial to his paintings) has been critically controversial. By examining The Garden of Earthly Delights, one may hope to understand a fragment of perhaps the greatest medieval artist.

The Garden of Earthly Delights triptych is probably the best example of his brilliance and artistic achievement, as well as of his transcendent incomprehensibility. The aim of this paper is to illustrate the various opinions and interpretations of this painting. I will briefly compare it to another work of Bosch, specifically The Haywain. I will also analyze one specific key segment of Earthly Delights to demonstrate the abundance and diversity of the commentaries. Finally, I will present my own interpretation of the painting, based upon a phrase that the artist himself found important.

Chapter One: Bosch's Triptychs

The purpose of a triptych is usually to illustrate a story, normally didactic and moral in theme, to educate, to enlighten, and obliquely, to sell. In a mostly illiterate society, art was an important way to communicate ideas. It was not simply for the highbrow and `cultural elite'. At a time when there was essentially a single religion, generally preached in Latin, art was a medium that would inspire and influence people. At the end of the Medieval Period, as Bosch painted, Erasmus wrote and Luther formulated his 95 theses, religion was decisively dominant in people's lives. God and Satan, Jesus and resurrection, Divine Judgment and punishment were not inconsequential ideas. People truly believed in these ideological concepts as well as fought and died for them.

Hieronymus Bosch was no heretic. The only fragments of information we know about him have come from the records of Illustre Lieve Vrouw Broederschap (Fraternity of our Illustrious Lady), where he was a respected member. Churches and very religious aristocrats (including the ultra-Catholic Philip II) bought his paintings. His triptychs (The Last Judgment, the Garden of Earthly Delights, the Haywain and the Temptation of Saint Anthony) are all moralizing statements. Hell is an overwhelming nightmarish, painful and fantastical place. The Garden of Eden is naturally beautiful, although dreamy and with eccentric symbolism. The middle panel, however, of the Haywain and The Garden of Earthly Delights, tell two powerfully different stories.

There is no doubt that the Haywain expresses a metaphorical and pessimistic view of life. The outer panel depicts a pilgrim, poor and world-weary, journeying through a world of crime and hardship. When the triptych is opened, the explanation is again relatively obvious. The subject is the Garden of Eden, beginning with the birth of Eve and ending with Adam and Eve being chased out by an angry, sword-bearing angel. The crucially significant and unique middle panel illustrates the fall of man and the reasons behind it. All is greed, and grasping for a bit of straw. Emperors, kings, popes and their courtiers follow the haycart, which is drawn by demons and monsters straight to Hell. There are several scenes of death, murder, and lust… in fact, many of the seven deadly sins as well as some of the minor ones are represented. At this, Bosch was a master. All this is being witnessed by Jesus, up in the clouds, tormented and confused by the conduct and activity below. There is one symbolic angel, on top of the hay wagon, looking to Jesus. Everyone else is ignoring Him, entirely enslaved to personal, baser aspirations.

On the third panel of both triptychs we are treated to a Boschian Hell. The symbolism, the suffering, the flames, the tortures and the demons are all there. Satan is not specifically depicted. The demons are hybrid monsters, straight from the creative genius of Bosch's imagination. The victims of this cruel world appear to be getting what they deserve due to their behavior here on earth. As with The Garden of Earthly Delights, the triptych ends on a horrific note. Mankind is essentially judged, incarcerated, and then punished forever.

The similarities and differences between these two works are what make them both interesting and educational. The left and right panels narrate essentially the same story. The left panel is Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. The right panel is Hell. Adam and Eve look nearly identical the same in both paintings. Certain demons are duplicated in the right panels. Yet the outside panel, which I believe would encapsulate the theme of the painting, and the central panel, which by its explosion of color and drama would illustrate the polemic, is the "key" to interpreting the world of Hieronymus Bosch. And Bosch, by his astute and sophisticated imagination, technical expertise and ultimate impenetrable symbolism has continued to defy all scholars that believe they have found this Rosetta Stone.

Chapter Two: Interpretations

Almost by definition, scholastic treatments of Bosch are confusing, biased and simply bizarre. Since there is essentially no way to definitively decipher a medieval artist who left behind no writings but embellished his works with enigmatic and cryptic symbolism, we are left with interpretations. Scholars want to understand what he was thinking, what he wanted to tell us, and why he created such mysterious masterpieces. Each symbol is conjectured to epitomize something about mankind's deepest fears, sins and joys. These representations are expected to be remarkably profound and meaningful. The artwork is astonishing. Yet the symbols are so puzzling, so diverse and so dazzling, that everyone who views a Garden of Earthly Delights interprets it with fervent subjectively.

For instance, the first author to describe the painting was Fra Jos¾ de Sigòenza in 1605. As a brother in a religious order, he obviously expressed his convictions in his explanation of the central panel. The Haywain illustrates the fall of man, and it is quite obviously due to a variety of sins. Therefore, de Sigòenza, as well as many after him, look to the central panel as an illustration of the justification for the fall of man. For the Garden of Earthly Delights he states, "These paintings are a satirical comment on the shame and sinfulness of mankind." This opinion predominates to this day.

Scholarly fascination with Bosch has flowered in this century. Interpretations of his works became intrinsically a prism, thereby which the biases of the authors became markedly pronounced. Twentieth century concepts were `projected' on his work, in ways not even this master of imagination, symbolism and obscurantism could realize. To illustrate this point, I have chosen the most famous and most eccentric interpretations of this century. Though this examination appears superficial, my intention is not to critique or deeply analyze any of the theories of these authors. My point is simply to portray the remarkable differences among the authors, specifically concerning the theme I want to develop. Then I plan on introducing my own theory. The names presented in bold are the most eminent.

The interpretations can basically be broken down into three schools: the sexual, the heretical, and the moralizing. Most authors fall into one of these categories. The first one to cite would be Max Friedlander, the art historian. In the late 1920's, he comments on the middle panel:

…Seen from a high vantage-point, the seemingly rising ground

supports a veritable forest of bodies --- nude men and women,

suggestively paired in crowded groups, in varied postures and

attitudes, behaving in the most curious fashion. At odds with

the description given, no orgiastic or erotic effect issues from

this propinquity, if only because the bodies seem almost spectral,

then too because they seem to be directed by some higher power,

and lastly because the curiously rebuslike presentation transcends

ordinary reality, turning aside crude sensuality by its filigree

delicacy.

Within a decade, Charles de Tolnay presented his somewhat Freudian views. For him, deciphering the symbols of the paintings should be viewed psychoanalytically, using theories about dreams and the subconscious.

A decade after that, in 1947 Wilhelm Fraenger published The Millennium of Hieronymus Bosch. His interpretation of the painting is brilliant, unique, and well researched. His theory, however, has always been controversial and has since been dismissed. It states Bosch was a member of the "Brothers of the Free Spirit" heretical sect (called Adamites). The middle panel is their ideal of a perfect community, where free and almost childlike love prevails. The people here are innocent and pure, living in a sanctified garden. This sexual freedom leads to salvation. His theory is in direct contrast to those that believe the central panel personifies the lust that will lead these people straight to hell.

Dirk Bax presented his own ideas concerning the Garden in 1949. He believed a great deal of Bosch's symbolism was influenced by Dutch sayings, songs and folklore. Members of his community could innately "read" the secret language of this triptych.

Jacques Combe introduced the idea of alchemy into the inspiration for Bosch's work. Laurinda Dixon would later employ many of his ideas in her work, Alchemical Imagery in Bosch's Garden of Delights. For example, she writes:

The principle subject is carnal love, lust which misleads man,

distracting him from his soul's welfare. In this way, Bosch's

attention is drawn anew to alchemistic symbols as it had been

in the case of the Temptation of St. Anthony. For alchemists

held the heretical notion that sexual duality was at the bottom

of the creation and evolution of this world.

In 1957, Dr. Tellez Carrasco blended motifs of existentialism into the Garden, blaming a metaphysical loneliness that would lead from boredom to melancholy to despair. Loneliness, however, does not seem to be an issue in this painting. In a different philosophical opinion, Charles D. Cuttler put an emphasis on Bosch's innate belief in the strength of mankind. He writes: "He stood to one side to comment with sardonic wit that the moral lesson is unread by mankind in general… The ultimate conclusion from Bosch's art is that like Sophocles' Oedipus, Camus' Sisyphus, or Faulkner's Dilsey, man must endure."

Andrea Peck wrote on the Jungian connotations of the triptych in 1963. Among the issues of forcing a Jungian psychoanalytical interpretation upon the work, she explores the world of dream imagery, alchemy, astrology, and the possibility of his Gnostic knowledge. She wrote:

…Yet nowhere else does the possibility that his message steps

beyond the pale of Christian morality seem so tantalizing. While most scholars uphold the orthodox view that the painting, like so many of his others, is an admonition against abandonment to earthly pleasure, foolishness, and sin, the arguments for an

ethereal interpretation remains compelling.

In 1967, Mario Busaggi wrote his interpretation:

…Even more than the terrifying Last Judgment at Vienna, this

painting seems to focus all the enigmas of Bosch's mind; to

decipher these, and accurately interpret their ambiguous aspects,

would be to put to flight all the shadows oppressing the

personality of this extraordinary creator of monsters and fantasies,

to throw light on some of the paradoxes of his character, and

above all to learn the fears, and possibly the guilt, which form an

integral part of it…Is there not a particular satisfaction inherent in

the treatment of these ethereal nudes - fleshy yet almost weightless,

fantastic yet realistic?

One of the oddest interpretations of Bosch's triptych is made by Erica Fromm in 1969. Her article is entitled, "The Manifest and the Latent Content of Two Paintings by Hieronymus Bosch: A Contribution to the Study of Creativity." She is analyzing the Garden, as well as the Haywain, from a psychoanalytic predilection. For instance, she writes:

While Bosch could allow his polymorphous perverse

fantasies to come close enough to consciousness to be observed

and made artistic use of by that ego, his fears about genitality

may have remained unconscious, yet crept into "The Garden of

Earthly Delights." Whatever Bosch may have meant to portray

consciously, he unconsciously revealed much about the dynamics

of his own personality. When one studies the two beautiful,

haunting, enigmatic paintings, one recognizes the tragedy of a

homosexual, and perhaps also of an impotent man who dreamt

and fantasized endlessly about all kinds of sexual pleasures; but

| whose punitive Super-Ego, severe castration fear, and sado-machochistic pre-genital fixation most likely prevented him from |

| having normal, lusty sexual relations. |

The extremes one may go to in an effort to decipher and explain The Garden of Earthly Delights is nothing new. In every century, each historian, each art critic, each person who visits the Prado Museum in Lisbon forms their own opinion. I would like to add a few more interpretations, simply to provide evidence that extravagant ideas, Bosch, interpretation and imagination are nearly synonymous. Then I will add my own theory, which is simply based on the very few words we can actually attribute to the artist.

Ludwig von Baldass, a prominent Bosch scholar, wrote the theme behind the Garden was simply a product of pessimistic medieval thought. Concerning the Garden, Baldass wrote:

The triptych as a whole, with opened wings, shows how sin,

came into the world through the Creation of Eve, how fleshly lusts

spread over the entire earth, promoting all the Deadly Sins, and

how this necessarily leads straight to Hell.

Bosch remains completely absorbed in the pessimistic view of life current in the late Middle Ages. He sees everything in the light of the approaching Last Judgment and can thus detect and demonstrate, in his strange and powerful visions, the close

connection between folly and sin, which are so often indistinguishable.

Elena Calas, in 1970, saw many of the portrayals as humorous, serene and fanciful. Puns and symbolism were employed in a mocking fashion, with a powerful yet pessimistic sense of humor. Laurinda Dixon, as previously mentioned, wrote an excellent book on the alchemical imagery in the triptych. It compares the mountains in the back to distillation equipment, and reorients his work into a pictorial narration of alchemical themes. She adds to and transcends the work of Combe by providing new interpretations and superior (all primary works) illustrations. Yet, as with everyone else, her interpretation falls short. Specifically, due to the Hell panel, it barely makes sense (on her terms, concerning relating the triptych to alchemical marriage, multiplication and putrification). This section, especially, appears forced. Alchemy was an important part of life during Bosch's age, since it defined medicine, chemistry and a quest for immortality as well as riches. It would not be surprising to find alchemical imagery in a painting by any knowledgeable medieval painter. But it does not provide the comprehensive key and the elusive answer.

Walter Gibson is one of the most renowned Bosch scholars. He believes, as did Fra Jos¾ de Sigòenza four centuries before, that the triptych is a depiction of the carnal, sinful life that will lead a man to hell. For example, he writes:

The Garden of Earthly Delights shows Bosch at the

height of his powers as a moralizing artist… In its didactic

message, in its depiction of mankind as given over to sin, the

Garden of Earthly Delights unquestionably belongs to the

Middle Ages. Likewise, in its iconographical programme,

encompassing the whole of history, betrays the same urge for

universality that we encounter in the fa¸ade sculptures of a

Gothic cathedral or in the contemporary cycles of mystery

plays.

This agrees with Anna Birgitta Rooth's idea that the Garden of Earthly Delights is actually based on The Vision of Tundalus, a Dantesque tale that was popular at the time. Marshall N. Myers wrote a book delineating the painting is actually based on the biblical book of Isaiah.

In 1984, Albert Cook released his theory based on linguistics and the structure of language. He concludes:

Bosch, however, creates his lexicon from `phonemes' of

separable iconographic elements, though his statement

simultaneously bodies forth distinct representational elements.

He offers langue and parole in a single, visually sealed field;

and he offers also the exhilaration arising from so powerful

an access to the innate properties of a communication in

images not tied to the seriality of words.

Gary Schwartz also has a biblical interpretation, although his is based on Genesis. He writes:

But this paradise is a far healthier place for mankind than the

one in The Last Judgment triptych. There was saw the rebellion

of the angels and the sins of Adam and Eve. These are missing

here. Instead, Bosch shows God blessing Adam and Eve. What

he said to them in the Bible was, "Be fruitful and multiply, and

fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the birds of

the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth."

If one decides to create a masterpiece based on the theme "Be fruitful and multiply", the Garden of Earthly Delights would be close to the ideal. Impossibly huge fruits are in evidence throughout. The "multiply" aspect is a foggier concept, as there are no children depicted. Sex, however, is an ever-present possibility. Though there may be no children at this point in the panel, there would have been if the panel was to be updated nine months later.

In the words of the scholar Sir Ernst Gombich: "The real or imaginary symbolic codes of alchemy, astrology, folklore, dream books, esoteric heresies and the unconscious have all been claimed, in isolation or in combination, to provide the solution." I think, however, the key is to be found in none of these. The answer is right there, obvious, on the front and central panels.

Chapter Three: My Interpretation

The previous chapter ascertained that there are an enormous number of conflicting and controversial theories about the Garden of Earthly Delights. The second chapter of this paper could easily be doubled, then doubled again, by describing interpretations. I would rather put forward one of my own. On the outside panel are words, from Bosch himself, to categorize its intent and significance. This is not unusual for medieval painting, but highly unusual for Bosch. This is one of the very few scraps of a written, (not simply pictorial) theme for Bosch. A triptych was meant to portray a story. In the front panel of the Haywain, Bosch portrayed a man experiencing a journey, metaphorically going through life. There are no words.

For the Garden of Earthly Delights, however, Bosch chose the ninth verse from Psalm 33. Ipse dixit et fact su[n]t - Ipse ma[n] davit et crata su[n]t. For He spoke, and it was; He commanded, and it stood.23

This would appear to be describing the central panel. The view is from a raised position, looking down upon mankind. The scenes portrayed in the left and right panels were customary representations for his audience. No explanation was needed. For the middle panel, however, a quick look at the alluded to Psalm would be of help. Now it makes sense. Bosch is portraying the middle of the Psalm (called A hymn of joy and praise to God)25 as the centerpiece of his work. It is God looking down upon his work, and they are blessed.

The following verse reads He fashioneth their hearts alike; he considereth all their works.26 On this point, nearly all of the authors agree, Bosch represented the most of the humans in the central panel as appearing nearly identical. They are all roughly the same age and could be brothers and sisters. There are no elderly or children. There are none of the cripples, wounded or angry people that Bosch delighted in dramatizing. There are a few black persons and one clothed one, but essentially they look remarkably twin-like. Overall, if one had to illustrate the concept of fashioning all hearts alike, this would be a good representation.

Considering their works is a different matter. I believe Bosch placed his own pessimistic view in the painting. People are in the hurried midst of doing nothing. They eat, speak, woo, ride horses in endless circles, crawl into eggs, and do a variety of useless activities. It was Bosch's cynical statement about the behavior of mankind.

In the end, the person or organization that the triptych was painted for desired a religious theme. A hymn of joy and praise to God would be perfect. The right and left panels illustrate a customary narrative. The central panel, arrayed with explosive color and imagery, is merely allegorizing the Psalm further than the front cover.

The intense delight Bosch places in symbols and creative expertise is his own personal touch. Though we will never know if he was an alchemist, a sado-masochistic deviant, a closet homosexual, a member of a "free-love" society, Leonardo's evil twin or whatever, we do know he was a great artist with an opinion he felt about the status of mankind, and the expertise to illustrate it.

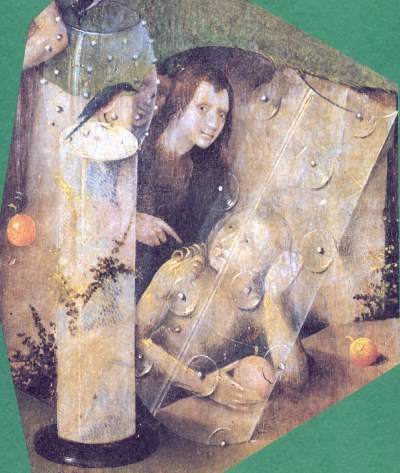

Conclusion: The Clothed Man

At the very bottom right of the central panel, there is one clothed man. He appears to be pointing at a woman enclosed in a glass tube. Since he was of the very few individuals staring directly back at the viewer, there is something intrinsically enigmatic about him. For one, why is he the only person clothed in the panel? Why is he pointing to the woman? Who is that figure lurking behind him? Why does he have an odd half smile? Why does the woman appear to have a dreamy expression and a flower in her mouth? Why do they appear to be in a cave, not in the garden proper?

Although it might seem that we had gained enough from

the historical point of view in being able to look into the face of

the man who commissioned such an extraordinary work of art

and inspired its intellectual conception, we can go even further

and make the conjecture that this portrayal of the bridegroom is

also that of the Grand Master of the Free Spirit, who meets us

with a piercing, scrutinizing gaze on the threshold of his

paradisical world. For when we consider such a self-confident

head, that of a man whose profound knowledge of the world

entitles him to occupy a position of very high authority, it is

impossible to think of any other person as the head of the Brethren

of the Free Spirit; and, similarly, only one who really was in the

chief position of authority would be entitled to reveal their

mystery - not only the community's erotic ideal, but the entire

edifice of its doctrine.

Anna Birgitta Rooth explained that the man was not wearing clothes, only he was hairy. From there she offers up the opinion that they were the "wild man" and "wild women" of literature. They could either be members of a foreign country or progenitors of the human race.

What I believe the man to be is in a more artistic vein. The person at the cave is Hieronymus Bosch. Though the chronology is a bit off, it is easy to believe that he wanted to paint himself as a younger man. To my knowledge, for whatever reasons, painters do not paint themselves in the nude. They have a touch of vanity about them, so perhaps this was the way Bosch signed his work. As God, from his heavens, viewed the earth, Bosch would want to be there. Not central, that would be the sin of pride. Certainly, he would not paint himself naked. The man behind him may be the donor or a friend. It is no more preposterous to assign his identity to Noah, John the Baptist, or the Grand Master of the Free Spirits.

The woman he points to may be his wife, Aleyt Goyaerts van den Meervenne. She was the marriage partner with the money. So perhaps he was indirectly but intentionally thanking her for his blessedness. If Bosch were placing himself into a work which describes the blessed, ideal state of mankind, he would want his wife next to him. He may be pointing to her, or simply tapping her on the shoulder. Perhaps it was his mistress or a daughter. This is a genuine mystery in an extremely cryptic piece.

Another interesting detail is that the facial structure does not resemble the Adam of the front panel as much as it looks like the Tree-Man (or so-called Alchemical Man) of the Hell panel. According to many authors, perhaps Adam desires to blame Eve by pointing to her. Yet upon close examination, it does not look like he is blaming her for anything. He is nearly smiling. He is one of the few people that actually appear like he can think for himself in this panel, that he is an individual, and that he does not care for this easy, childlike, perhaps sinful life. Perhaps that is the meaning of the cave. That is why I believe the clothed man was a Bosch self-portrait, symbolizing his independence.

11/16/99

Bibliography

Baldass, Ludwig von. Hieronymus Bosch. New York: Harry N. Abrams,

Inc., 1960.

Bax, D. Hieronymus Bosch. Rotterdam: A.A. Balkema, 1979.

Beagle, Peter S. The Garden Of Earthly Delight. New York: The Viking

Press, 1982.

Bergman, Madeleine. Hieronymus Bosch and Alchemy: A Study on the

St. Anthony Triptych. Stockholm: Almquist & Wiksell International,

1979.

Beuningen, Charles van. The Complete Drawings of Hieronymus Bosch.

New York: St. Martin's Press, 1973.

Bosch, Hieronymus. Jheronimus Bosch [Catalogue of an Exhibition held

Noordbrabants Museum, `s-Hertogenbosch, Netherlands, 17

september - 15 november 1967. s'-Hertogenbosch, Netherlands:

Hieronymus Bosch Exhibition Foundation, 1967.

Bussagli, Mario. Bosch. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1967.

| Cinotti, Mia. The Complete Paintings of Bosch. New York: Harry N. |

Combe, Jacques. Jerome Bosch. Paris: Editions Pierre Tisn¾, 1957.

Daniel, Howard. Hieronymus Bosch. New York: The Hyperion Press, 1947.

Delevoy, Robert, L. Bosch. New York: Crow Publishers, Inc., 1960.

Dixon, Laurinda, S. Alchemical Imagery in Bosch's Garden of Delights.

Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1980.

Elkins, James. "On the Unimportance of Alchemy in Western Painting."

Konsthistorisk tidskrift; revy fÀor konst och konstforskning 61(1992):

21-6.

Franger, Wilhelm. The Millennium of Hieronymus Bosch. London: Faber

And Faber, Limited, 1952.

Friedlander, Max. Early Netherlandish Painting: From Van Eyck to Bruegel.

New York: Phaidon Publishers, Inc., 1956.

Friedlander, Max. Early Netherlandish Painting Vol V: Geertgen tot Sint

Jans and Jerome Bosch. Leyden, The Netherlands: A.W. Sijthoff,

1969.

Gibson, Walter S. Hieronymus Bosch. New York, Washington: Prager

Publishers, 1973.

Guillaud, Jacqueline and Maurice. Bosch: The Garden of Earthly Delights.

New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1989.

Harris, Lynda. The Secret Heresy of Hieronymus Bosch. Edinburgh: Floris

Books, 1995.

Hemphill, R.E. "The personality and problem of Hieronymus Bosch."

Offprint: Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 58 (Feb.

1965): 137-144.

Jowell, Frances. "The paintings of Hieronymus Bosch." Offprint:

Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 58 (Feb. 1965): 131-

136.

Linfert, Carl. Hieronymus Bosch. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1971.

Martin, Gregory. Hieronymus Bosch. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1979.

Merten, Ernst. Hieronymus Bosch. Bristol, England: Artlines UK, Ltd.,

1988.

Mullins, Edwin B. "The Despair of Hieronymus Bosch." The Daily

Telegraph London: Oct. 10,1966. 52-56.

Orienti, Susan and Rene de Solier. Hieronymus Bosch. New York: Crescent

Books, 1979.

Rooth, Anna Birgitta. Exploring the Garen of Delights: Essays in Bosch's

Paintings and the Medieval Mental Culture. Helsinki: Academia

Scientiarum Fennica, 1992.

Schwartz, Gary. Hieronymus Bosch: First Impressions. New York: Harry

N. Abrams, Inc., 1997.

Snyder, James, ed. Bosch in Perspective. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentiss

Hall, Inc., 1973.

Staniº, Micheal M. Hieronymus Bosch. London: Tiger Books International

Limited, 1988.

William Coventry