| William W. Coventry |

| Possession & The Courts 1593-1692: |

| Salem in Context |

|

| Witches and Possession | |

One of the most dramatic, memorable, and ultimately baffling aspects of many witchcraft trials concern the category of the “possessed,” or in the terms of the time, the “afflicted” or “bewitched.” This was certainly true with Salem, where the afflicted were the major catalysts of the proceedings. Their hysterical and unnerving behavior sparked and drove the trials. The spectacle of young girls screaming, crying, choking, and convulsing in court as they accused innocent people of sending murderous specters to harm them created an enormously compelling scene. To appreciate fully the events at Salem, one must understand the fundamentals of possession, its history, and its place in the courts and in society.

In possession cases, usually female children or adolescents fell into remarkably similar and disturbing behavioral patterns. Predominant symptoms included convulsions, feelings of being pinched, bitten or pricked, loss of speech, hearing or appetite, breathing problems, hallucinations and abnormal vocalizations. This presented the sufferer's family with a truly terrifying situation. As historian Barbara Rosen writes, “The sudden emergence, in a docile and amenable child, of a personality which raves,

screams, roars with laughter, utters dreadful blasphemies and cannot bear

godly utterances - or alternatively, withdraws into complete blankness - seems, even today, like the invasion of an alien being.”

When faced with such symptoms with no discernable natural cause or cure, people occasionally diagnosed witchcraft. They would identify, accuse and try a witch (usually, but not always, an elderly and troublesome woman). In the belief system of the day, the witch was responsible for the affliction. To decipher these extraordinary cases, people called on doctors, clergymen and magistrates. Authors wrote Demonologies, along with new laws to judge these unusual cases. As author and professor G.S. Rousseau wrote:

| Meticulous courtroom procedures were developed throughout Europe to winnow true demoniacs and witches from those erroneously or falsely accused - those whose prima facie manifestations of possession were due to other causes - to illness, accident, suggestion, or even fraud. Expert witnesses were heard, especially physicians; often these were the same physicians who were compiling medical definitions of hysteria. |

Possession and the casting out of demons have existed since biblical times. In fact, employing scriptures to both understand and treat the affliction became customary. Though in the New Testament only a single or few symptoms afflicted the possessed, these behaviors merged by the medieval period to create a stereotypical persona. Cases of possession developed medical and legal implications as well. By the sixteenth century, these issues, medical, legal and religious, became thoroughly interwoven.

Genuine possession was difficult to determine. The causes and symptoms were complex, culturally specific and subject to interpretation. Multi-causal motivations on the part of both the spectators and the possessed included political, religious, or social manipulation, greed, intense spirituality, malice, frustration, or even desire for attention. Historian H. C. Eric Midelfort commented on the need to consider physical or mental illness:

| I think it likely that demonic possession provided troubled persons with the means of expressing their often guilty and morally straining conflicts, a vocabulary of gestures, grimaces, words, voices, and feelings with which to experience and describe their sense that they were not fully in charge of their lives or their own thoughts. One cannot rule out the Protestant or materialist suspicion that demoniacs were being coached by their exorcists and confessors on how best to appear as if possessed, but such charges of fraud and priestcraft only seem compelling if we have prematurely excluded the possibility (or even the probability) that the demon-possessed were actually suffering from a serious disorder of body, mind, and soul. |

There were solid medical explanations for many of the symptoms. Epilepsy, “the sacred disease” had been described by Hippocrates two thousand years previously, as was hysteria (a Greek word meaning `uterus') Hysteria has a long, complex, and controversial history.

The author Ilza Veith believes the ancient Egyptians described aspects of hysteria as far back as the Kahun Papyrus (around 1900 B.C.), Describing the symptoms, she writes:

| These and similar disturbances were believed to be caused by “starvation “ of the uterus or by its upward dislocation with a consequent crowding of the other organs… the thinking ran that in such situations the uterus dries up and loses weight and, in its search for moisture, rises toward the hypochondrium, thus impeding the flow of breath which was supposed normally to descend into the abdominal cavity. If the organ comes to rest in this position it causes convulsions similar to those of epilepsy.” |

The Greeks believed that the uterus of a woman with an unsatisfactory sex life could wander throughout the body, causing symptoms of hysteria. Plato writes in Timeus that the womb is an animal that desires to bear children, and “When it remains barren too long after puberty it is distressed

and sorely disturbed and straying about in the body and cutting off the passages of the breath, it impedes respiration and brings the sufferer into the extremist anguish, and provokes all manner of diseases besides.”

This was the same defense the physician Edward Jorden used in his description of Mary Glover sufferings three and a half millennia later (see Chapter 4). Not until the seventeenth century did the etiology of hysteria seriously turn to mental and nervous considerations (see Chapter 5, in which we will also take a longer look at the medical theories concerning possession). Without modern medical psychosomatic theory, people occasionally, under certain conditions, blamed these afflictions on witchcraft. We will examine some of the circumstances that produced accusations of witchcraft.

There was little doubt during the early modern period in Europe about the existence of witches, devils, and possessed individuals. The belief that Satan was present on earth and caused all sorts of calamities was common. Did Satan need witches as intermediaries to possess people? Could witches summon demons to do their commands? Was there a legitimate pact between them? Since the worldview of early modern Europeans contained mysterious wonders, the investigations of these sinister and supernatural relationships took on a profound importance. As G.S. Rousseau states, “From the late fifteenth century, in a movement peaking in the seventeenth, authorities, ecclesiastical and secular alike, commandeered the courts to stop the epidemic spread of witchcraft, and concomitantly clamp down on the rise of hysteria it was engendering.” Paradoxically, the publicity these possession trials created may have spurred the interest on.

In 1563, the Cleves physician Johanne Weyer published De praestigiis daemonum, which included several cases of demonic possession. Several cases arose in convents and many of the symptoms (appalling vocalizations, contortions, convulsions, lewd body movements, loss of appetite, etc.) were similar to cases examined later in this work. With his abundance of clinical experience, he concluded people could not cause possession, even alleged witches. Weyer did not believe in the existence of actual witches. Though people deluded themselves into believing that they had supernatural and dangerous power, they actually did not. According to Weyer, the possessed were either naturally ill, possessed by demons, lazy, taking a mixture of drugs, or were faking.

Though little read or appreciated in his own time, Weyer is highly regarded today for his compassionate and relatively modern views on mental illness and witchcraft. As a result of his focus on mental illness, he bears the title of a founder, even a father, of modern psychiatry. Other views of his are typically medieval; such as there are seven million, four hundred nine thousand, one hundred and twenty seven demons, commanded by seventy-nine princes.

In France, a succession of politically and religiously motivated “show trials” exploited cases of possession between 1562-1634. The instigators of these trials manipulated the possessed, usually nuns, into very dramatic and public exorcisms and trials. Trials involving possessed nuns occurred at Aix-en-Provence (1611), Lille (1613), Loudun (1634), and Louviers (1642). All resulted from accusations of witchcraft. The most famous case occurred at Loudon from 1630-34. Powerful enemies of Father Urbain Grandier accused him of bewitching the entire Ursuline convent at Loudun, including the Mother Superior. Though Grandier was well connected, his opponents conspired to stage-manage the nuns and exorcisms, forge evidence and use political influence for revenge. His adversaries had him burned alive at the stake on August 18, 1634.

One difference between the French possessions at the convents and the “afflictions” occurring in England and colonial America was the lurid sexual theatrics of the French nuns. They raised their habits, begged for sexual attention, used vulgar language, and made lascivious motions. At Loudon, a local doctor, Claude Quillet, considered the disorders “…hysteromania or even erotomania. These poor little devils of nuns, seeing themselves shut up within four walls, become madly in love, fall into a melancholic delirium, worked upon by the desires of the flesh, and in truth, what they need to be perfectly cured is a remedy of the flesh.” English trials, which we will be examining in the next chapter, were much less prurient.

Though there have been many theories regarding possession by anthropologists, physicians, sociologists, historians and others, its causes are still nebulous. An all-encompassing explanation for possession does not exist, for a variety of reasons. One principal impediment is that we do not exist in a culture that takes the concept of possession for granted. Possession was one of the “wonders” of the time, dramatically drawing upon itself all sorts of spiritually based explanations. Cases of individual possessions were debatable, but there was no doubt of Satan's ability to possess a human being. Though we may look at cases and judge them egregious frauds, obvious expressions of neurosis or as pathetic attempts at gaining attention, our assumptions are not theirs. Many times the most intelligent, erudite and respected members of the community were critically investigating the bewitched person to see if they were “dissembling.” It was not something taken lightly.

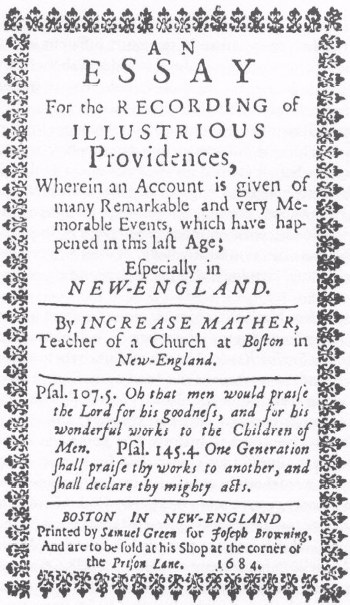

According to their worldview, Satan was so powerful and zealous he would never stop trying to overthrow God's creation. The authors of the era capitalized on possessions to demonstrate their spiritual expectations. When the possessed spoke, their audience considered the message a revelation. The Greeks believed this as far back as their Sybil. People listened and endeavored to decipher any veiled meaning. A good example of this would be the Puritans of New England. Increase and Cotton Mather recorded their astonishing “providences” and “wonders” for the edification of the public (see Chapters 7 & 8). Unfortunately, this intensely spiritual vision of New England, coupled with some disastrous secular circumstances, helped set the stage for the Salem witchcraft trials.

The attempt to find meaning and purpose in possession could lead to unexpected results. Ministers could see “providences” when there was none. To possess a young girl would be not only easy and desirable for Satan on an individual basis, but symbolically it could be seen as what he could do to the Christian world. Once innocent, then tormented in a vicious and painful “life or death” struggle against a supernatural power, the possessed individual became a visible metaphor for the world. The historian James Sharpe believes people viewed possession:

| …as a battle between good and evil taking place around the contorted and writhing body of the afflicted. Narratives of possession, therefore, remind us of the sheer complexity of witchcraft as a cultural and social phenomenon in early modern England, while the phenomenon of possession itself remained firmly lodged in the popular and medical consciousnesses until well into the eighteenth century. |

There is a variety of possibilities why someone would act possessed. They could gain power and attention. As the psychologist and author Nicholas Spanos writes, “Those who became demoniacs were usually individuals with little social power or status who were hemmed in by numerous social restrictions and had few sanctioned avenues for protesting their dissatisfactions or improving their lot.”

In this paper, I am mainly concerned with the youthful female accusers in the following trials. We see in their patterns of behavior certain

“rewards” given for acting a certain way. By acting out socially improper behavior while possessed, they would not only be exempt from punishment but also actually receive additional love and attention. They would become a principal actor in a real dramatic piece, with an audience (acquaintances and family) and a possible savior (clergy, doctors or magistrates). They could create a powerfully affecting show, as long as they recognized and responded to clues consciously or unconsciously provided by the spectators.

In his book Servants of Satan, the historian Joseph Klait's description about Salem could apply to all the possessed girls in the following trials:

| The possessed of Salem were adolescent girls living in a highly restrictive domestic environment that was ripe for interpersonal conflict, depressive states, and delusions. Possession allowed these young women to unconsciously act out forbidden fantasies and to relieve deep guilt feelings in the spotlight of benevolent concern from their superiors. For as long as they remained bewitched, they were not obscure village girls. The attention lavished on them was a great contrast to the repression and indifference they had formerly experienced. |

| Patterns of English Witchcraft Trials |

|

Throughout the medieval period, jurisdiction over witchcraft in England presided in an ecclesiastical milieu. Since the church was not allowed to harm life, limb or properties, the sentences, largely, were relatively scarce and mild (certainly in regard to the Continental Europe). Involving itself with witchcraft, the secular arm passed three Acts of Parliament, in 1542 (repealed 1547), 1563 (repealed 1604) and 1604 (repealed 1736). English accusations and punishments differed a great deal from the Continent (though Scotland was an exception). Except for the Matthew Hopkins period (1646-7), trials rarely exploded into ever-expanding accusations against neighbors. “Maleficium”, or causing harm by supernatural means, was the predominant witch-oriented anxiety among the English populace. This contrasts with Continental concerns, such as Devil-Worship, infant cannibalization or riding to Sabbaths on brooms. Though the educated could blend in their more Continental beliefs, presumptions of a conspiracy between witches and Satan were less prominent. Another reason why English trials did not proliferate as intensely was that torture was illegal in England (except in cases of treason). Getting a confession without torture proved quite difficult.

The Acts also allowed for lesser punishments for lesser crimes. England had a trial by jury structure, not an inquisitorial system of justice. The court could not identify a crime, initiate a trial nor decide the verdict. The judge, in theory, was to remain impartial.

The stereotypical English witch was much like the Continental version. According to the modern historians Keith Thomas and Alan Macfarlane, and the sixteenth-century writer Reginald Scott (among others), witches were generally older women, usually poor, unsightly and argumentative. They were social outcasts, reliant upon the good will and generosity of their neighbors for survival.

These unfortunates were not simple beggars. A system of Christian neighborly obligations promoted this cooperation. By refusing to give this charity, conflicts and tensions could ensue. The borrower may curse or mumble as they walk away. Later, misfortune might occur to the person who disregarded their communal duty. Blaming the needy neighbor for this hardship was satisfying for a variety of reasons. Perhaps the person who denied their obligation was feeling guilty. On the other hand, the person could truly believe their neighbor was a witch. Deciding upon witchcraft as the cause, the identification of the witch responsible was almost immediate. Most accusations of witchcraft were against near neighbors. Identification did not always led to directly to trial. Prosecutions, however, may not take

place for years. Gossip, tensions, suspicions and fears festered in these communities. A modern estimate states only one in three instances of bewitchment led to an indictment. Many, if not, most of the witchcraft trials began this way.

Several good examples of this occurred at Chelmsford, in Essex County between 1566 and 1589. The first Chelmsford trial (there were four) occurred a mere three years after the Act of 1563. The accusations against Mother Waterhouse, her daughter Joan and Elizabeth Francis ranged from causing a neighbor to lose her curds to murder. A twelve-year-old girl testified that after she had refused to give Joan Waterhouse some bread and cheese, a black dog with an ape's face and horns on its head came and asked her for some butter, speaking evil words. In the court's interpretation, the dog became one of Mother Waterhouse's familiars. She also had a witches' mark. The court found Joan not guilty while sentencing Elizabeth Francis to two years imprisonment. The court also had the 63-year-old widow Waterhouse hanged.

Witchcraft trials also occurred in Chelmsford 1579 and 1589. Three hangings occurred after the first one, including that of Elizabeth Francis. At

least four hangings took place after the second one, mainly on the evidence of children. All of the executed were female. All three Chelmsford trials included testimony concerning animal familiars. Therefore, the concept of children accusing older women of witchcraft and about keeping familiars, so prominent at Salem, was nothing new.

In 1582, fourteen women from St. Osyth, very near to Chelmsford, stood trial for witchcraft. Like the other trials, this one also included several features significant to English witchcraft. Crucial again to these trials are the inclusions of children's testimony and the concept of a familiar (or imp). Charged and executed for using witchcraft to murder three people in the previous two years, a midwife and “white” witch, Ursula Kempe, had a unique defense. She testified, “though she could unwitch, she could not witch.” The manipulation of her eight-year-old son into describing his mother's imps forced Kempe into readjusting her defense. Promised leniency if she confessed, Kempe did so. Her execution quickly followed.

An indirect significance of these Chelmsford area trials was the

influence they had on a nearby gentleman estate manager, Reginald Scot (1538-1599). In 1584, Scot self-published his The Discoverie of Witchcraft, a truly pioneering book in skepticism regarding witchcraft. In it, he found four categories of witches. The first two was if a person accused of being a witch was either innocent or deluding themselves. The other two categories were for poisoners or charlatans. Though there was nothing supernatural about it, the last two groups contained “witches” and deserved punishment, Therefore, the first two categories, the majority, did not deserve punishment. Though influential to a small number of skeptics, Scot's work had many powerful opponents. King James I may have had the book burned, and wrote his Demonology possibly in response to it. The research of several modern historians have agreed with Scot's sixteenth century observations:

| One sort of such as said to bee witches, are women which be commonly old, lame, bleare-eied, pale, fowle, and full of wrinkles; poore, sullen, superstitious, and papists; or such as knowe no religoun: in whose drousie minds the divell hath gotten a fine seat; so as, what mischeefe, mischance, calamitie, or slaughter is brought to passe, they are easily persuaded the same is done by themselves….These miserable wretches are so odious unto all their neighbors, and so feared, as few dare offend them, or denie them anie thing they aske…They go from house to house, and from doore to doore for a pot full of milk, yest, drinke, pottage, or some such releefe; without the which they could hardlie live… |

| It falleth out many times, that neither their necessities, nor their expection is answered or served, in those places where they beg or borrowe; but rather their lewdnesse is by their neighbors reproved. And further, in tract of time the witch waxeth odious and tedious to hir neighbors; and they again are despised and despited of hir: so as sometimes she cursseth one, and sometimes another…Doubtlesse (at length) some of hir neighbors die, or fall sicke; or some of their children are visited with diseases that vex them strangelie: as apoplexies, epilepsies, convulsions, hot fevers, wormes, &c. Which by ignorant parents are supposed to be the vengeance of witches. Yea and their oinions and conceits are / confirmed and maintained by unskilfull physicians…Witchcraft and inchantment is the cloke of ignorance… |

| Though these generalizations fit many of the situations, it is important to remember that the reasons for witchcraft accusations could be complex and ambiguous. Young women, as well as men and children, were accused. Ministers, teachers, bailiffs and magistrates occasionally were charged. There could be accusations between families of equal social standing, possibly due to political or economic rivalry. Simple malice, resentment or criminal conduct could be behind an accusation. Charges of operating diabolical power even went as high up the political ladder as Cardinal Wolsey, Anne Boleyn and Oliver Cromwell. As Malcolm Gaskill writes, “Most of all, witchcraft demonstrates the hostility early modern people could feel for others, how they interpreted ill-will, and how many pursued grudges with a degree of ruthlessness shocking to modern sensibilities.” |

| James I (1566-1625) is a good example of this ambiguity over witchcraft. As James IV of Scotland, he was originally zealous in his prosecution of witches. He believed a coven of witches had attempted to murder him and his new bride while the royal couple was sailing between Denmark and Scotland by raising storms. Three hundred witches supposedly met and concluded a pact with the Devil. During these trials (of the North Berwick witches), he originally believed the witches to be lying. He changed his mind when one of them revealed to him the private conversation James had with his wife on their wedding night. As the trials were essentially about treason, James allowed some horrific tortures and eventually a large number of executions took place. |

| In 1597, James published his Daemonologie, possibly to counter Scot's The Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584), and Joann Weyer's De Praestigiis Daemonum (1563). It was a compendium of existing beliefs on witchcraft, including the Devil could take the form of animals, women were more predisposed to evil than men, witches could cause illness and that the “swimming” test was effective. Of course, they could also raise storms. Nevertheless, James was gradually becoming more tolerant and skeptical of witchcraft accusations. |

| In 1603, James IV of Scotland assumed the throne as James I of England. Parliament passed a new Witchcraft Act the following year. Though quite similar to the previous Acts, the first offense of witchcraft now carried the death sentence. Evoking of evil spirits could bring the death sentence, whether maleficium occurred or not. |

| Though the Act exhibited a harsher degree of sentencing, James' skepticism helped to dampen witch-hunts. He personally exposed a number of frauds and told his son to continue this policy. During his twenty-two year reign, less than forty executions for witchcraft took place. Excepting the Matthew Hopkins years, twenty years after James' death, this low amount of executions continued in England. |

| The Matthew Hopkins episode (1645-1646) presents a troubling deviation in the history of English witchcraft. During the midst of the English Civil War, Hopkins, with his assistant John Stearne, initiated a witch-craze with the illegal use of torture and compelling confessions to include a list of accomplices. With the normally integrated procedures of government and justice in turmoil, approximately two hundred executions occurred. By marshaling public sentiment and insecurity into a witch-craze, Hopkins and Stearne made a good amount of money for their efforts. Unlike earlier trials in England, the confessions included tales of sexual intercourse with the Devil, along with the concept of a written pact with the Devil and a witches' Sabbath. Both Hopkins and Stearne wrote pamphlets, but their careers ended as abruptly as they began. People no longer either trusted them or wanted to pay for their services. Hopkins died of tuberculosis in 1647. |

| Several characteristics of these trials are similar to Salem. The political turmoil abetted and manipulated the accusations. The conflict metamorphosed into apocalyptic dimensions. The parliamentarians were viewing the royalists not merely as political enemies, but as agents of the Devil. The Salem worldview also incorporated apocalyptic terms, albeit placing the culpability on different enemies. A special Court of Oyer and Terminer was set up in both situations. |

| The unique dynamics and beliefs concerning witchcraft were gradually changing. Authors such as John Wagstaffe and John Webster published books condemning and mocking the belief in witches. Accusations and trials continued sporadically, but rarely did an execution take place. Though judges may have believed witchcraft theoretically possible, they increasingly felt they did not have enough legitimate evidence to convict. As the seventeenth century continued, however, |

| most judges did their utmost best not to convict. The populace continued to harass, accuse and even murder people for witchcraft, but this was illegal and punishable. |

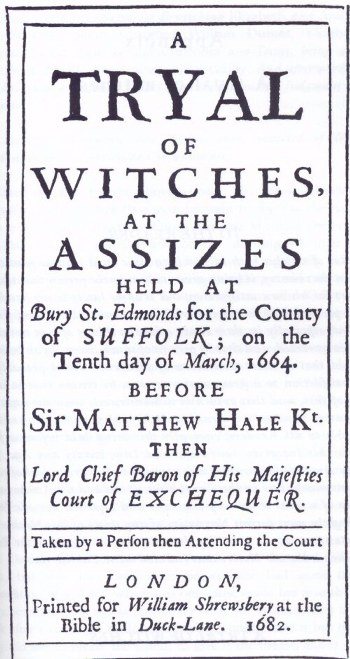

| For example, Lord Chief Justice, Sir Matthew Hale, renowned to this day, hanged two witches in 1664. We will look at this case in Chapter VI. His successor, Sir John Holt (in office from 1690-1702), treated accusations of witchcraft with heavy skepticism. He consistently influenced jurors against convicted accused witches, sentencing no one for witchcraft. In 1685, the execution for witchcraft (Alice Molland) occurred in England. |

| Although historian Brian Levack is speaking about Europe as a whole, his opinion also specifically fits Britain, “What brought the trials to an end was not simply a recognition that witch-hunting could get out of control, but a series of significant changes in European judicial systems, in the mental outlook of the educated and ruling classes, in the religious climate that prevailed throughout Europe, and in the general conditions in which people lived.” |

| The Witches of Warboys |

|

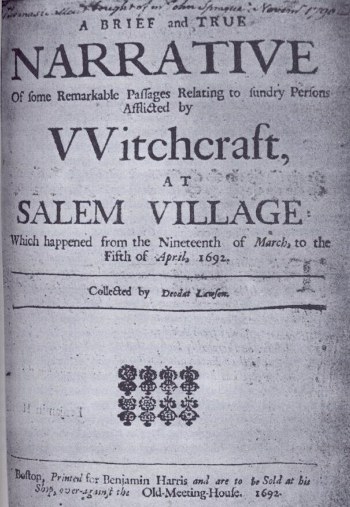

In 1593, a trial occurred in Warboys, England that eerily evoked the Salem trials ninety-nine years later. It provides an ominous template of a repertoire of recognizable and socially understood behaviors that tragically came together. The unusual physical and mental symptoms, the swooning and contortions, the doctor's diagnosis of witchcraft, the spreading of the fits to other females, the ages of the accusers, the credence given to children's testimony, and their inability to see, hear or feel produced a tragic archetype for a possession trial. Nothing quite like it had occurred before. As historian D.P. Walker wrote, “…this is certainly a case of considerable importance, in that it was known to later demoniacs and their healers, and is the first notorious instance of possessed children and adolescents successfully hunting witches to death.”

The parish of Warboys, Huntingdonshire, is seven and a half miles northeast from Huntingdon and eighty miles north of London. It is also less than forty miles east from Bury St. Edmunds, where another famous possession trial took place (see Chapter 6). A small village at the time of the trial, its population only surpassed one thousand after 1800. Today it contains 8435.5 acres with a population of 3169.

The Throckmortons moved into their Warboys manor house on September 29, 1589. They were pious, prestigious, and powerful. Members of the extended family wielded considerable influence both at the Elizabethan court as well as locally in the community. Robert Throckmorton was a close friend with Sir Henry Cromwell, one of the wealthiest commoners in England and grandfather of the renowned Oliver. This was in great contrast to the Samuels, the accused witch family. The Samuels, neighbors of the Throckmortons, were at the bottom rung of society. Impoverished, of lowly reputation, and poorly educated, they did not have the abundant resources of friends, family, and status that the Throckmortons possessed. The conflict between the families began within six weeks of the Throckmorton's arrival.

All our information about the trial comes from one widely read pamphlet, published a year after the trial. Entitled The most strange and admirable discoverie of the three Witches of Warboys, arraigned, convicted, and executed at the last Assizes at Huntington, for the bewitching of the five daughters of Robert Throckmorton Esquire, and divers other persons, with sundrie Divellish and grievous torments, it affected thinking about “bewitchment” for following generations. It appears to have several authors,

possibly the afflicted Throckmorton children's father, uncle, and doctor. Naturally, it presented only the Throckmortons' version of the events. The author or authors describe the original symptoms:

| About the 10th of November in the year 1589 Mistress Jane, one of the daughters of the said Master Throckmorton being near the age of 10 years [she was in fact 9 years and 3 months] fell upon a sudden into a strange kind of sickness of body, the manner whereof was as followeth. Sometimes she would sneeze very loud and thick for the space of half an hour together, and presently as one in a great trance or swoon lay quietly as long; soon after she would begin to swell and heave up her belly so as none was able to bend her or keep her down; sometimes she would shake one leg and no other part of her, as if the palsey had been in it, sometimes the other; presently she would shake one of her arms, and then the other, soon after her head, as if she had been infected with the running palsey. |

The parents first believed it might be “falling sickness,” epilepsy. When the elderly Alice Samuel came to visit, Jane accused her of being a witch. Up to this point, the parents had shown considerable restraint. Seeking a natural explanation for their child's afflictions, two respected doctors, one a physician from Cambridge, examined Jane and diagnosed witchcraft. The Throckmortons were new to the area and did not feel anyone had reason for the bewitching. The pamphlet continues:

| Within less than a month after that, another sister younger than any the rest, about the age of nine years, fell into the like case, and cried out of Mother Samuel as the other did. Soon after, Mistress Joan, the eldest sister of them all, about the age of fifteen years, was in the same case and worse handled indeed than any of the other sisters were; for she having more strength than they, and striving more with the spirit than the rest, not being able to overcome it was the more grievously tormented. For it forced her to sneeze, screech and groan very fearfully; sometime it would heave up her belly, and bounce up her body with such violence that, had she not been kept upon her bed, it could not but have greatly bruised her body…being deprived of all use of their senses during their fits, for they could neither see, hear, nor feel anybody, only crying out of Mother Samuel, desiring to have her taken away from them, who never more came after she perceived herself to be suspected. |

These symptoms were considered characteristic of either hysteria or possession. Nevertheless, the frightful convulsions, the inability to see, hear or feel, and the children's sudden extreme behavior (along with the doctors' opinions) swayed the diagnosis towards witchcraft. This began a dangerous and bizarre antagonism between the powerful Throckmorton family, driven by the children's affliction, and the Samuel family, helpless yet defiant.

On February 13, 1590, the first test took place at the Throckmorton manor. In front of several members of the Throckmorton family, Alice Samuel, her daughter Agnes, and a Cicely Tyson underwent the “scratch” test from Jane Throckmorton. According to the folk wisdom of the time, scratching a witch reputedly alleviated the bewitched person's afflictions. This action also confirmed the witch's guilt. Jane refused to scratch Cicely (who was never mentioned again) and Agnes. Alice's presence, however, drove the child into a violent frenzy, and , “…presently the child s scratched with such vehemency that her nails brake into spills with the force and ernest desire that she had to revenge. Master Whittle, a friend of the Throckmortons, attempted to restrain the nine-year-old:

| …but that she would heave up her belly far bigger and in higher measure for her proportion than any woman with child ready to be delivered, her belly being as hard as though there had been for the present time a great loaf in the same; and in such manner it would rise and fall an hundred times in the space of an hour, her eyes being closed as though she had been blind and her arms spread abroad so stiff and strong that the strength of a man was not able to bring them to her body. |

| These continual fits, convulsions, and astonishing strength, along with |

| the previous symptoms, provided physical evidence for the observers that the possession was real. The intense scratching demonstrated to them that proximity to Alice Samuel proved dangerous. The following day, February 14, for their own safety, the children left Warboys to live with relatives. Elizabeth Throckmorton, aged about 14, resided at the home of her uncle, Gilbert Pickering. Here, Elizabeth stated she saw the spectral image of Alice,“…in a white sheet with a black child sitting on her shoulders which makes her tremble all over, and she calls on uncle Master Pickering and others to save her…” Elizabeth also believed the spectral Alice tried to force a demon into her mouth. This demon took a variety of forms of small animals, described as either a cat, mouse, or toad. Elizabeth also despised scripture readings, in fact, “…any good word (if any chanced to name God, or prayed God to bless her, or named any word that tended to godliness),” caused fits to occur. |

| The children's attempt at recovery at their relatives failed, and they returned home approximately a month later. When Lady Cromwell, the wife of the Samuels' landlord and a friend of the Throckmortons, visited about this time (March, 1590), the children flaunted their symptoms. She |

| took Alice Samuel aside and berated her for causing such affliction. An argument ensued in which Lady Cromwell grabbed a pair of scissors and cut a lock of hair off Alice. She gave it to Mrs. Throckmorton to burn. This was a folk remedy to weaken a witch's power, much like scratching. |

| Mrs. Samuel, naturally feeling insulted, asked, “Madam, why do you use me thus? I never did you any harm as yet.” That very night, Lady Cromwell had nightmares about Alice Samuel. She fell ill and died slightly more than a year later (July, 1592). After her death, the children accused Alice Samuel of causing it. Those present at the altercation remembered Alice's ominous “… as yet.” The “murder” of Lady Cromwell eventually legitimized the executions of the Samuels, as the Witchcraft Act of 1563 allowed capital punishment of convicted witches if their actions resulted in death. |

Throughout November, the children continued their afflictions. Speaking through the girls, the “demons” said they, “…waxed weary of Mother Samuel [and that] now ere long they would bring their Dame either to confession or confusion.” The children decided upon an unconventional course of action. They convinced their parents that they felt well enough to live with Alice present (as she could not feed or communicate with her imps). Alice Samuel was forced to live at the Throckmorton's home in a type of quasi-legal house arrest. This extraordinary situation of the afflicted requiring the company of the accused witch occurred at no other trial we will examine.

The children's power over the situation became absolute. They told Alice Samuel “that they shall not be well in any place except in her house, or she be brought to continue with them; and besides that, they shall have more troublesome fits than ever they had…” For the next three weeks, into December, the children “…had very many most grievous and troublesome fits; insomuch that when night came, there was never a one of them able to go to their beds alone, their legs were so full of pain and sores, besides many other griefs they had in their bodies…”

Robert Throckmorton realized Alice would have to live in his household. He offered John Samuel ten pounds to hire the best servant in Huntingdonshire in return for letting Alice reside at the Throckmorton manor. Samuel refused and for one day, Robert had the children live at the Samuel's small residence. John Samuel threatened to freeze and starve the children, but finally relented:

| …Master Throckmorton still to continue in the same mine aforesaid, he [John Samuel] was contented to let his wife go home with them that night, who went all to Master Throckmorton's house very well together, and so continued the space of nine or ten days following, without any manner of soreness, lameness, or any manner grudging of fits, and in better case than they had been (as it was well known), all of them together, for the space of three whole years before. |

The confrontational situation had continued for three years before Alice moved in, with the children usually afflicted and Alice essentially held responsible. The stress must have been considerable. And yet the Throckmortons had yet to seek recourse to the law. Even the new living arrangements, however, proved unsatisfactory for the children. They now said Alice was feeding the imps (which only they could see) when no was looking. Their fits returned, even in Alice's presence. The adults were now fully manipulated by the whims, sufferings and imagination of their children.

Though the girls exhibited several frightening physical ailments (convulsions, great strength, etc.), they also demonstrated what could be considered childish willfulness and behavior. Refusals to listen to prayers and readings from the Bible, and stubbornness over eating habits, are actions today that may be considered childhood rebellion. One of the sisters, Elizabeth ate only if taken to a nearby picturesque pond. Elizabeth, “…delighteth in play; she will pick out some one body to play with her at cards, and but one only, not hearing, seeing or speaking to any other…”

However, there is no way to tell if this situation was a desire for attention or not. The element of feigning possession for “sport” also occurred at Salem. This behavior puzzled adults then as well as now. It could also be one of the reasons the Throckmorton parents spent three years investigating the cause of their children's afflictions. Skepticism concerning genuine bewitchment is characteristic of many trials.

For almost the remainder of 1592, Alice Samuel lived at the Throckmorton's in an increasingly nerve-wracking situation. Robert Throckmorton came to believe Alice could predict when the fits would occur. With the children present, and though she was “very loath” to foretell anything, Robert pressured her into revealing, “One of them shall have three

fits (naming the child) such and such for the manner (namely, easy fits, appointing the time for their beginnings and endings); the other shall have two in like sort (the time appointed by her); and the third shall have none but be well all the day.” As she had stated, the children suffered accordingly. Not surprisingly, this made Alice appear even guiltier.

Finally, the emotional stress became too much. Alice Samuel broke down and confessed on December 24, 1592 at the Throckmortons and again at church the following day. Upon hearing this, her husband and daughter forced her to retract her confession. This withdrawal angered and embarrassed Throckmorton, who took the Samuels to court. All three Samuels became suspects, which corresponded to the contemporary common belief that witchcraft ran in families. This period of adult recriminations, confessions and retractions and dramatic fits and outbursts from the children lasted until April, 1593.

The presence of specters was another feature shared by both the events at Salem and Warboys. Unlike the fear that specters produced from the girls at Salem, Joan Throckmorton spoke with her spirits as she would “imaginary friends.” Named Blue, Pluck, Catch, and three Smacks (who were cousins), and supposedly sent by Mrs. Samuel, they were said to control Joan's fits. On February 10th, 1593, Doctor Dorington, the rector of Warboys and Robert Throckmorton's brother in law, noticed this conversation. Apparently talking to herself, since no one else could see the spirits, she would says things such as, “…What doest thou say…that I shall now have my fits when I shall both hear, see and know everybody? That is a new trick indeed!”

On April 4, 1593, the trial took place at nearby Huntingdon. According to the pamphlet, at least five hundred people viewed the proceedings and the afflictions. The children vividly continued their fits until each Samuel stated, with slight variation, “As I am a witch and did consent to the death of the Lady Cromwell, so I charge the devil to suffer Mistress Jane to come out of her fit at this present.” Though John Samuel refused at first to affirm this, Judge Fenner threatened him with immediate execution. Agnes Samuel, the daughter, bravely accepted her fate. Upon hearing the Samuels' oaths, the children immediately became well. With their admission of guilt, Judge Fenner ordered them hanged on April 6th.

The significance of the Warboys case lies in the malicious creativity of the girls, the influence of the trial and the pamphlet, and its deadly outcome. The popularity of the pamphlet and the infamy of the Warboys witches inspired other cases (most notably the Gunters in 1608 - described in the following chapter). The physician and author John Cotta (described in Chapter 5), normally skeptical concerning cases of possession, believed the Warboys witches to be guilty. The historian George Kittredge calls the Warboys case “…the most momentous witch-trial that had ever occurred in England,” partially because it “… demonstrably produced a deep and lasting impression on the class that made laws.” He makes a strong case that the Warboys trial influenced the passage of the Witchcraft Bill of 1604.

Many symptoms similar to those the Throckmorton girls suffered afflicted other young females throughout the next century. Only a small percentage of these fell under the rubric of possession. As the historian Moira Tatem illustrates Warboys by quoting Sir Walter Scott's view of the trial, their opinions could be accurate for nearly any of the cases we will be examining:

| Concocting the charade must have been exciting, and offered a wonderful opportunity to break out of the stifling bonds of the intensely religious household. It also won them gratifying attention in a totally male-dominated society, attention which adolescents in general often crave. But as time went on it became more and more difficult to admit the truth, as Scott rightly said, …they had carried on the farce so long that they could not well escape from their own web of deceit but by the death of these helpless creatures. |

The credulity and beliefs of parents, doctors, clergy, and magistrates would continue to be tested. Eventually, Salem would be the finale of the hangings of accused witches, based on the disturbing testimony of afflicted young girls.

Edward Jorden & the Mary Glover Case

Though the Warboys trial affected a few highly placed members of English society and may have contributed to the Witchcraft Act of 1604, the next case surpassed it in notoriety and influence. Widely known and discussed throughout London, the Mary Glover/Elizabeth Jackson case occurred in 1602. Powerful members of the English religious and political community, as well as several members of the Royal College of Physicians, opposed one another in court. Whether Elizabeth Jackson could bewitch Mary Glover became an affair of national interest. As Michael McDonald comments, “Glover's spectacular fits, her accusations of witchcraft against an old woman called Elizabeth Jackson, the dramatic trial and conviction of the `witch' and Glover's eventual dispossession by a group of Puritan preachers had captured the attention of London's leading citizens, enraged the church hierarchy and alarmed the government.”

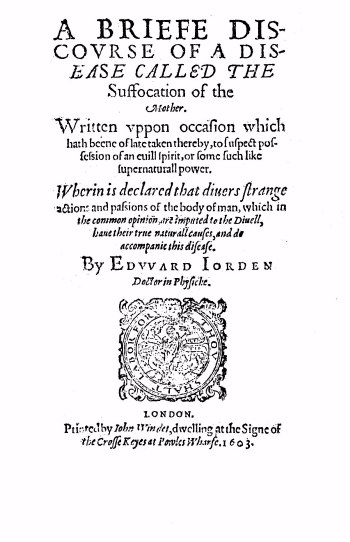

Fortunately for historians, their quarrels and opinions survived in three pamphlets, all published within a year of the trial. Two of these, Dr. Steven Bradwell's Mary Glovers Late Woeful Case and John Swan's A True and Brief Report of Mary Glovers Vexation, argued that Mary Glover was bewitched. The author of the third, Dr. Edward Jorden, contended that the symptoms Mary suffered were due to “suffocation of the mother” (a disease similar to hysteria). The judge disagreed, convicted Jackson, and humiliated Jorden. Six months after the trial, Jorden published A Briefe Discourse of a Disease Called the Suffocation of the Mother. Though Jorden did not discuss the case specifically, he expanded upon the defense he had used.

Observed for centuries, the symptoms of “suffocation of the mother” included choking (with frightful throat swellings), convulsions, regularly timed fits, paralysis, and unnatural vocalizations. Theories based on a “wandering womb” orientation had been around for a thousand years (see Chapter 4). In the “Epistle Dedicatorie” of his book, Jorden described how medically explainable the symptoms were, in contrast to the supernatural:

| There also you shall find convulsions, contractions, distortions, and such to be ordinarie Symptoms in this disease. Another signe of a supernaturall power they make to be the due & orderly returning of the fits, when they keepe their just day and houre, which we call periods or circuits. This accident as it is common to diverse other chonicall diseases, as headaches, gowtes, Epilepsies, Tertians, Quartans &c. so it is often observed in this diesease of the mother as is sufficiently proved in the 2nd Chapter. Another argument of theirs is the offence in eating, or drinking, as if the Divell ment to choake them therewith. But this Symptom is also ordinarie in uterin affects, as I shew in the sixt Chapter: and I have at this time a patient troubled in like manner. Another reason of theirs is, the coming of the fits upon the presence of some certain person. The like I doe shew in the same Chapter, and the reasons of it, from the stirring of the affections of the mind. |

According to Steven Bradwell, a member of the College of Physicians, it began in April 1602, when fourteen-year-old Mary Glover gossiped about her unsavory neighbor, the elderly Elizabeth Jackson (a beggar and reputed witch). The enraged Jackson shrieked horrifying curses at Glover, who left quite shaken. During the early modern period, curses were considered dangerous, especially from an alleged witch. Their angry mumblings threatened forthcoming maleficium. Not only did the person cursed often believe it might work, but the witch could have as well.

Within days, Mary began to experience several symptoms, including dumbness and blindness, throat constriction, intense fasting, frequent abdominal distortions, apparent unconsciousness, spasms, and convulsions. Mary's parents, well connected in the community, believed it at first to be a medical condition. Thomas Moundeford, President of the College of Physicians seven times, examined Mary and originally diagnosed it as an unidentified, but natural, disease. Jackson, however, boasted to several people about the illness she had brought upon the girl, saying, “I thanck my God he hath heard my prayer, and stopped the mouth and tyed the tongue of one of myne enemies”.

Elizabeth Jackson bragged in the household of William Glover, a relation of Mary's and a city alderman. For the next several months, family and friends staged several experiments and confrontations between Mary and Elizabeth at several residences. Like the Salem and Warboys trials, these well-attended meetings became spectacles. As Michael Macdonald writes, “The house was jammed with people: pious Puritans awestruck by the evident power of Satan, more skeptical observers wanting to see for themselves whether Glover's illness was natural or supernatural and the merely curious.” Experiments designed to illicit a physical response included hot pins applied to Mary's cheeks and burning paper to her hands. Mary's insensitivity confirmed affliction caused by the supernatural. A further experiment disguised Elizabeth's identity. Despite this, Mary's fits ensued. Stephen Bradwell, described Mary's symptoms in Mary Glovers Late Woeful Case:

| …she was ever taken with an other Crying fitt; wherein was no deprivation of her senses, but only her eyes and tongue restrayned, together with such a huge extension of her throate, as was monstruous to behould: with Crying yelling and striyving with her body…but if the ould woman came unto her, as she lay upon the bed, especially if she touched her flesh, or her garments, the mayds body would (sometimes) wallow over unto her, other sometimes, rising up in the middle, rebounding wise turne over, unto her, her elbowes being then most deformedly drawen inwards, and withall plucked upwards, to her Chin; but the handes and wrests, turned downwards, and wrethed outward; a position well becoming the malice of that efficient [cause]. This tumbling, or casting over towards the witch, when she came to the bedside, or touched her, was at the first two tryalls very palpably playne, and towards her only; … in this fitt, the mouth being fast shut, and her lipps close, there cam a voyce through her nostrills, that sounded very like (especially at some time) Hange her, or Honge her. |

These experiments led to a trial on December 1st, 1602. Certainly, some of these symptoms appeared naturally; others were associated with bewitchment. Other symptoms, such as the vocalized “hang her,” appear intentionally malicious. More experiments occurred at the trial to determine whether Mary was “dissembling.” A repeat of the burning test helped authenticate her possession. The experiments concerning the ability to quote scripture reappeared at Salem.

| After dinner the Lo. Anderson Mr. Recorder of London, Sir William Cornwallis, Sir Jerome Bowes, and diver other Justices went up into the Chamber, to see the mayde; before whome went the Towneclerke, with som officers; with thundring voyces crying; bring the fyre, and hot Irons, for this Counterfett; Come wee will marke her, on the Cheeke, for a Counterfett: but the senseles mayde apprehended none of these things. After the Justices had considered the figure, and stiffenes of her body, Mr. Recorder againe [Fol. 32r] with a fyred paper burnt her hand, until it blistered. Then was Elizabeth Jackson called for, At the instant of whose coming into the Chamber, that sound in the maides nostrils, which before that time, was not so well to be distinguished, seemed both to them in that Chamber, and also in the next adjoining, as plainely to be discerned, Hang her, as any voice, that is not uttered by the tongue it selfe can be… The Lord Anderson then commanded Elizabeth Jackson to come to the bed, and lay her hand upon the maide; which no sooner was done, but the maides body…was presently throwen, and casted with great violence. The Judge willed the woman to say the Lordes prayer; which by no means she could go through with, though often tryed…” |

Lines misspoken from the Lord's Prayer drove Mary into convulsions. Naturally, this implied Jackson's guilt. Not only had Jackson bewitched Mary, but also these convulsions dramatically demonstrated her witchery for the courtroom. Bradwell describes the striking confrontation, along with the medical perplexities involved:

| These be things that Galen, (no, nor Hippocrates,) never saw in phisick, and therefore I am sure, he must no more than they, that can assigne them place within the compasse of our profession. But well doth this signe, challenge his fire, by other like cases reported of Demoniacks, by Wierus, and the booke of the witches of Warboys: where, at the invocating of the name of Jesus, the parties afflicted were suddainly moved, or tossed and one especially, I find to have bene troubled, at those very wordes, in like sort, deliver us from evill. |

Weirus (Weyer) and the witches of Warboys appear earlier in this paper. The theories of Galen and Hippocrates are briefly described in the following chapter. These two sentences demonstrate how significant and firmly rooted this trial is in the literature of possession and the medical explanations for it.

Even with Jackson disguised and Mary blindfolded, once again, fits ensued only if Jackson was present. Though this evidence convinced others, including Bradwell and Judge Anderson, that Glover was bewitched, Jorden testified that it was “suffocation of the mother.”

Unlike the other trials we will examine, this one contained strong political and religious ramifications. In the other trials, everyone involved belonged to the same religion; only some were more active than others were. This one involves strained relationships between Catholics, Puritans, and Anglicans. The powerful Anglican Bishop of London, Richard Bancroft, objected to anything suggestive of Catholicism, such as exorcism. Puritans and Catholics viewed this case, among others, as a way to validate their beliefs. Mary's grandfather, executed during the Marian persecutions, provided a martyred backdrop. This religious and political quandary is far too involved for examination in this study, but suffice it to say, the trial meant more than diagnosing a fourteen-year-old's afflictions.

The doctors were deadlocked. Some thought Mary to be faking; others thought she was ill, still others believed her to be bewitched. From the bewitchment position, there could be no doubt of the illness' supernatural symptoms. In a moment reminiscent of “The Exorcist,” Bradwell relates:

| In so much, as when one of the preachers, in the middest of those blasphemous abusions of Godds goodly image, prayed God to rebuke that foule malicious divell, she suddenly (saith the storie) though blinde, dumbe and deafe, turned to him, and did bark out froath at him. So did she to others that stood over her, cast out foam, up to their faces; her mouth being wide open. There is no cause, that I can understand, whie the suffocation of the mother should have been in such a chafe. |

During a rebuke to Jorden's diagnosis of “Passio Hysterica” (another name for “suffocation of the mother”), Judge Anderson stated: “Divines, Phisitions, I know they are learned and wise, but to say this is naturall, and tell me neither the cause, nor the Cure of it, I care not for your Judgement: geve me a naturall reason, and a naturall remedy, or a rash for your physic.”

Judge Anderson detested witchcraft and in his jury summation stated, “This land is full of witches…I have hanged five or six and twenty of them; there is no man here can speak more of them than myself…This woman hath that property; she is full of cursing, she threatens and prophesies and still it takes effect; she must of necessity be a prophet or a witch”. The jury agreed with the judge, and Jackson received the maximum sentence for a first time conviction of witchcraft under the 1563 Witchcraft Act, one year in jail and four stands at the pillory.

Though Elizabeth Jackson lost in court, it is quite possible she never served her sentence. Due to the religio-political ramifications of the trial, very powerful supporters came to her defense. Bishop Richard Bancroft commissioned several pamphlets, including Jorden's Brief Discourse, to buttress Anglican doctrines. In December 1602, Mary Glover was finally “cured,” during an all-day session of fasting and prayer, as ministers battled the devil in Mary. At the dramatic conclusion, she supposedly cried out with the same words her grandfather used when executed, “he is come, he is come… the comforter is come, O Lord thou hast delivered me.” The malevolent spirit left her. Mary had symbolically gone from possessed to saintly.

Four years later, Jorden, summoned by James I, examined Anne Gunter (who alleged three female neighbors bewitched her). James had become far more skeptical concerning witches since his days in Scotland. He took pride in detecting fraudulent cases of witchcraft. Many of her symptoms were the same as the Glover case, although Gunter also vomited pins. Through a series of tests, some used earlier on Glover, Jorden concluded she was faking. Anne even met James, who offered her an indemnity if she confessed. Gunter admitted to being coached and using the Warboys pamphlet for ideas concerning possession. She confessed her father had put her up to the dangerous ruse. She herself believed she was suffering from “the mother.” Anne apparently married and her father received a lengthy jail sentence.

Though Jorden's book is a significant contribution in the battle against superstition, providing a reasonable, natural account for illnesses such as Glover's, the diagnosis itself floundered upon flawed anatomical theory. The concept of a “wandering womb” became unviable once the dissection of female cadavers became acceptable. The arrangement of muscles and organs negated any possibility of a “wandering womb.” Nor did many people read A Brief Discourse; in fact, Michael MacDonald calls Jorden, “one of the most celebrated obscure physicians in medical history.”

Jorden was a man of his times who argued against superstition and for rational, scientific explanations. Though several symptoms Jorden had to diagnose in these trials bear a resemblance to those suffered at Salem, and although Judge Anderson was an uncompromising witch hater, the verdict itself demonstrates a certain rationality and even moderation. It was possible Elizabeth Jackson served no time and mended her ways. No hysteria occurred, no attempt force a confession or implicate others took place. Reputations and households were not irredeemably ruined. Moreover, no executions followed a conviction based on the testimony of children.

The meaning and importance of this case becomes evident by comparing it with Salem. Occurring eighty years before, in London, the capital and epicenter of the British Empire, it was politicized, significant and discussed. The prevailing opinions of the King and his court influenced, but

did not control, the outcome. Some of the tests used, and many of the

symptoms Mary suffered, reappear at Salem. If we look for an increasing progression of “enlightened” thinking traversing though the seventeenth century, this trial reveals the error. At the very beginning of the century, a convicted witch suffered a relatively minor punishment for afflicting a child. At the end of the century, nineteen people hanged because of similar symptoms, similar beliefs, and a similar judicial system.

Medical Beliefs Concerning Hysteria and Witchcraft

At this point in the paper, it would be appropriate to discuss some of the medical theories that appear applicable to these young girls. In each case of possession we examine, a physician performed an examination. The vast majority of possible possession cases did not advance past a doctor's examination. Physicians usually found natural causes responsible for the symptoms. Doctors' opinions, however, varied greatly, especially as the century progressed.

By profiling four doctors at separate points throughout the century, we get a sense of each physician's understanding of possession. These physicians were not personally involved in witch trials. Reading their opinions provides us the opportunity to delve into a world medically and spiritually far different from our own. In our post-Freudian world, it is impossible to categorize the afflicted from a purely psychological perspective. Our inability to physically examine them leaves us with the written opinions of contemporary doctors. Nor can we truly understand the deeply religious environment that could foster such distinctive symptoms. We can establish, however, a tenuous advancement in medical theory from the supernatural to the natural, from the superstitious to the scientific, throughout the century.

Carol Karlsen describes the main symptoms of the possessed girls in New England as, “…strange fits, with violent, contorted body movements; prolonged trances and paralyzed limbs; difficulty in eating, breathing, seeing, hearing, and speaking; sensations of being beaten, pricked with pins, strangled or stabbed; grotesque screams and pitiful weeping, punctuated by a strange but equally unsettling calm between convulsions, when little if anything was remembered and nothing seemed amiss.” These ailments are also symptomatic of the afflicted girls in England.

In the period we will be examining, not only did the specific symptoms vary case-by-case, but also the type of diagnosis varied with the type of practitioner. Apothecaries, white witches, cunning folk, surgeons, university-trained physicians, and clergy, as well as family and friends, treated illnesses. People went to whomever they trusted, whom they could afford, or who had a reputation for healing. Many thought illnesses were a punishment from God. The examination of urine, consciences, and horoscopes constituted diagnosis. The treatment could be equally as diverse.

The practice and theory of medicine progressed exponentially over the seventeenth century. This evolution, however, was uneven, chaotic, and

inchoate. The Renaissance rediscovery of classical medicine, with its emphasis on the four humors and based on the works of Galen and Hippocrates, slowly gave way to more modern theory. The iatrochemical and astrological theories of Paracelsus gained and lost popularity. Historian Leland Estes theorizes this muddled situation actually promoted witch-hunts, as “the rise of the craze could be traced to the revolution in medical thinking that marched beside it so closely” and that the medical revolution “might very well have provided both its intellectual form and its emotional impetus.” Simply put, according to Estes, as medicine gradually became more “modern,” the lack of a predominant and credible medical doctrine to diagnose illness made a witchcraft accusation more plausible.

Religion and medicine deeply intertwined in the causes and cures of illness. Both doctors and clergy were interested in the wellness of the soul. Treatment for disorders such as madness, epilepsy, and hysteria were applied as if a third person or a deity was involved.

A case in point would be Jorden's diagnosis of Mary Glover. Half of the physicians testifying, along with the judge, believed Mary was bewitched. Jorden and Dr. John Argent, eight times President of the College of Physicians, did not. A third person (a witch) was involved. Jorden believed, however, he found a rational, medical explanation for the disease. Based on a flawed theory of female anatomy, the premise of "suffocation of the mother" died out by the end of the century, especially after the work of Drs. Willis and Sydenham. Jorden states the choking sensation is caused by “… the rising of the Mother wherby it is sometimes drawn upwards or sidewards above his natural seate, compressing the neighbour parts” This “wandering womb” concept existed for centuries. Many of the accusers in the trials we will examine experienced several symptoms of “the mother,” also called “passio hysterica” and “suffocatio,” a reasonable diagnosis for the time.

Even Shakespeare was aware of the disease. Though there is some disagreement as to the lines' intent, Shakespeare had King Lear (1608) state:

| O! how this mother swells upward toward my heart! |

Thy elements below.

Doctors from Hippocrates to Freud and beyond employed the nebulous term of hysteria, with causes and cures altering with each author. In England and Colonial America during the period we are examining, a condition with some of the symptoms of hysteria could be considered caused by witchcraft. Doctors wrote pamphlets on how to distinguish natural from supernatural causes. They also argued against non-physicians as healers, such as the clergy. Their emphasis was on disseminating medical knowledge, not theological interpretations of what a troubled person's disease “meant.”

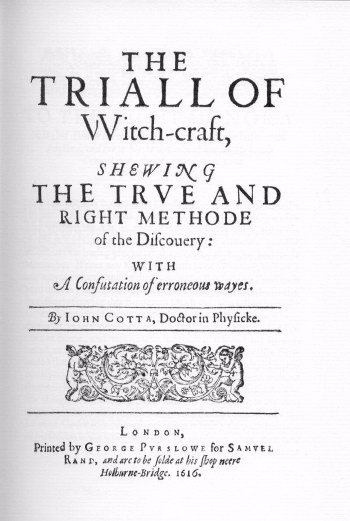

John Cotta (1575? -1650?)

With the publications of A Short Discoverie of the Unobserved

Dangers of Several Sorts of Ignorant and Unconsiderate Practisers of Physicke in England (1612) and The Triall of Witchcraft, showing the true Methode of the Discovery with a Confutation of Erroneous Ways (1616), the respected physician John Cotta attempted to warn the public about abuses and misunderstandings about witchcraft. He believed physicians should be the ones diagnosing witchcraft and possession. Cotta believed the touch test (used extensively at several trials, including Salem) to be a charade. Increase Mather quoted this opinion in his Cases of Conscience. Cotta stated:

| We will first herein examine the touch of the suppposed Witch, immediately commanding the cessation of the supposed fits of the bewitched. That this is a false or Diabolical miracle and not of God, may be justly doubted. |

Cotta examples from his own cases to press for natural causes of illness. In 1608, he treated the daughter of a nearby gentleman. She regularly had a “vehement shaking and violent casting forward of her head”, “ending with a loud and shrill inarticulate sound of these two syllables `ipha, ipha'”. Cotta decided it was a type of “falling sickness,” probably epilepsy or some other convulsive, but natural, disease. After a brief recovery, she

became much worse. He writes:

| …I learned that their daughter after diverse tortures of her mouth and face, with staring and rolling of her eyes, crawling and tumbling upon the ground, grating and gnashing her teeth, was now newly fallen into a deadly trance, wherein she had continued a whole day, representing the very shape and image of death, without all sense or motion: her pulse or breathing only witnessing a remainder of life. |

After this description, Cotta realized a diagnosis of witchcraft was feasible in this case. Personally, however, he believed his own experience, coupled with that of previous writers, treated such symptoms as natural. He then describes symptoms that give the appearance of witchcraft:

| This is seen commonly in falling sicknesses, diverse kinds of convulsions, and the like. In these diseases, some bite their tongues and flesh, some make fearful and frightful shriekings and outcries, some are violently tossed and tumbled from one place unto another, some spit, some froth, some gnash their teeth, some have their faces continually deformed and drawn awry, some have all parts wrested and writhed into infinitely ugly shapes. … Some have their limbs and divers members suddenly with violence snatched up and carried aloft, and after suffered by their own weight to fall again. Some have an inordinate leaping and hopping of the flesh, though every part of the body. In some diseases the mind is as strangely transported into admirable visions and miraculous apparitions, as the body is metamorphosed into the former strange shapes. In many ordinary diseases, in the oppressions of the brain, in fevers, the sick usually think themselves to see things that are not, but in their own abused |

| imaginary and false conceit…. Sometimes they complain of devils or witches, lively describing their seeming shapes and gestures toward them. |

| Like Jorden, Cotta had seen all these symptoms previously, in natural illnesses. He then lists his “proofs” to decide if a case is actually due to witchcraft: |

| The most certain and chief proofs of witchcraft & devilish practices upon the sick, among the learned esteemed are generally reputed three: First, a true and judicious manifestation in the sick of some real power, act or deed, in, above and beyond reason and natural cause. Secondly, annihilation and frustration of wholesome and proper remedies, with discretion and art administered, without any just reason or cause thereof.Thirdly, ought either in the knowledge or speech of the diseased, discovering a ravishment, possession or obsession of their minds or spirits by any infernal inspiration. Hence the sick often speak strange languages unto themselves unknown, and prophecy things to come, above human capacity. |

The significant idea to remember is that Cotta is trying to categorize witchcraft as an unlikely instrument of illness. Although Cotta firmly believes in witchcraft and the Devil, by using the diagnostic “test” outlined above, he decides upon natural causes in case after case. Strangely enough, more than one woman voluntarily confessed to bewitching the gentlewoman.

Even though they were “dying for sorcery”, he, like Weyer before him, came

to the uncommon conclusion that they deceived themselves. Unlike Weyer, Cotta states, "I grant the voluntary and uncompelled, or duly and truly evicted confession of a witch, to be sufficient condemnation of her self, and therefore justly has the law laid their blood upon their own heads, but their confession I cannot conceive sufficient eviction of the witchcraft itself...” If the doctors and magistrates at Salem had Cotta's extraordinary and medically based skepticism, the conclusions could have been drastically different. The people swearing to their innocence would have a much better chance of survival than those that confessed.

Edward Drage (1637? -1669)

In 1665, Edward Drage wrote about an interesting case where mental illness appears to be involved. Mary Hall's peculiar symptoms appear to be a mixture of hysteria and possession. The excerpt is from: Daimonomageia: A Small Treatise of Sicknesses and Diseases From Witchcraft and Supernatural Causes, Never before, at least in this comprised Order, and general Manner, was he like published. Being useful to others besides Physicians.

| Mary Hall, a Maid of Woman's Stature, a Smith's Daughter of Little Gadsen in the County of Hertford, began to sicken in the fall of the Leaf, 1663. It took her first in one foot, with a trembling shaking and convulsive motion, afterwards it possessed both; she would sit stamping very much; she had sometimes like Epileptick, sometimes like Convulsive fits, and strange ejaculations; she was sent to Doctor Woodhouse of Berkinsted, a Man famous in curing bewitched persons, for so she was esteemed to be; he seeing the Water and her, judged the like, and prepared stinking Suffumigations, over which she held her head, and sometimes did strain to vomit, and her distemper for some weeks seemed abated upon Doctor Woodhouse direction. |

| In this first paragraph, we see several characteristics of hysteria (hysterical tremors, abnormal movements, seizures). We also see the available medical practices, examining the urine, and applying fumigations to the head (to drive “the mother” back down). Odd vocalizations then occurred, as Mary began imitating cats, dogs and bears. “Spirits” spoke through her in an unnatural voice: |

| The manner and matter of the Spirits speaking was on this wise: If any said Get thee out of her, Satan; the Spirit replied We are two; and as often as any said, Satan or Devil, it would reply, “We are two”; and would say, We are only two little, Goodwife Harods, and Youngs; sometimes we are in the shape of Serpents, sometimes of Flyes, sometimes of Rats or Mice; and Goodwife Harod sent us to Choak this Maid, Mary Hall; but we should have choaked Goodman Hall, but of him we have no Power, and so possessed his daughter. |

| In an interesting embellishment to the possession, like the Warboys case, “imps” were present. These dangerous demons, however, were inside Mary. They told her to choke herself, to drown herself, and to throw herself into the fire. She had difficulty in breathing and her throat swelled. The demons spoke through her without moving her lips. Like |

| most possession cases we will examine, Mary also demonstrated an aversion to the word of God, “But when People prayed, they tore and tormented her; yet at sometimes they lay still, and if she sat, on a suddain they would make her leap up a good height; sometimes in length she would leap an Extraordinary way… |

| Like Cotta, Drage lists his “proofs” to determine witchcraft. Drage is more likely than Cotta to diagnose witchcraft as the culprit. Cotta would have considered this evidence unacceptable, in fact, he specifically argued against the use of the swimming test (dunking suspected witches in water, usually rivers, to see if the water `rejects' them as supernatural - if they sink they are innocent). |

| We think it necessary here to write down some discoveries of Witches according to the manifold examination we have took of experienced People. |

| 1.From their swimming. 2. From their Teats. 3. From their non-ability to call upon God as others do. |

| Drage did not satisfactorily conclude the Mary Hall case. We do not find out if Mary Hall recovered. No mention of a suspected witch occurred. We are left with “If Mary Hall is falsely possessed, it doth not prove another not to be truly possessed; or if Mary Hall be truly possessed, it doth not prove that there are no such counterfeits.” |

| Thomas Willis (1621-75) |

| A highly regarded physician and neuroanatomist, Willis believed specific parts of the brain handled separate tasks. The “circle of Willis” is named after him. One subject he investigated was the etiology of hysteria. He began his chapter “Of the Affects which are vulgarly call's Hysterical” with, “If at any time an unusual sort of Sickness, or of a very Secret Origine occurs in the Body of a Woman, so that its Cause lies hid, and the Therapeutick Indication be wholly uncertain, presently we accuse the evil influence of the Womb (which for the most part is guiltless) and in any unusual Symptom; we cry out that there is somewhat hysterical in it; and consequently the Physical intentions and the uses of Remedies are directed for this end, which often is only a starting hole for Ignorance.” Instead of blaming symptoms on the “Ascent of the Womb” he believed, “. the affect call'd Hysterical, chiefly, and primarily is Convulsive, and depends principally on the Brain and the Genus Nervosum being affected.” This was a positive, though incomplete, step away from the purely spiritual or entirely physical causes of hysteria. |

| But if when any person is distempered there be a suspicion of Witchcraft or Fascination, there are chiefly two kinds of motion which are wont to create and maintain it; viz. First, if the Patient uses such Contortions and Gesticulations of the Members, or of the whole Body, which no found Man, even a Mimic, or any Tumbler, is wont to imitate; And secondly, if he exerts a strength, which exceeds all human force, to which if there be joyn'd excretions of monstrous things, as when heaps of Pins are cast up, or living Animals are voided by siege, it comes to be without dispute that the Devil has, and acts his part in this Tragedy. |

In the end, Willis emphasized skepticism towards the supernatural. He wrote, “…Grant this I say, yet all kinds of Convulsions which appear prodigious, as being besides the common course of this Disease, ought not presently to be imputed to enchantments of Witches, or tricks of the Devil, for often, though appearing strange, they proceed from meer natural causes, and stand in need of no other Exorcisms for a Cure, than Remedies which are wont to be prescribed against Convulsive affects…”

Thomas Sydenham (1624-89)

Perhaps the finest clinician of his time, Thomas Sydenham's reputation acclaims him as the “English Hippocrates.” He relied upon personal diagnosis and bedside manner, without much faith in experimental theories. Like Willis, he examined hysteria, though he reasoned the cause of the disease as principally psychological. Sydenham published his influential work on hysteria, Epistolary Dissertation, in 1682. He believed it was more widespread than previously thought:

| Of all the chronic diseases hysteria - unless I err - is the commonest; since just as fevers - taken with their accompaniments - equal two thirds of the number of all chronic diseases taken together, so do hysterical complaints (or complaints so called) make one half of the remaining third. As to females, if we except those who lead a hard and hardy life, there is rarely one who is wholly free from them - and females, be it remembered, form one half of the adults of the world. Then, again, such male subjects as lead a sedentary or studious life, and grow pale over their books and papers, are similarly afflicted; since, however much, antiquity may have laid the blame of hysteria upon the uterus, hypochondriasis (which we impute to some obstruction of the spleen or viscera) is as like it as one egg is to another. True, indeed, it is that women are more subject than males. This, however, is not on account of the uterus, but for reasons which will be seen in the sequel. |